While most articles about marine heads start with a humorous anecdote involving a bottle of Purell, I’ll instead begin this ditty with a description of the first truly impressive head that I saw.

Caveat emptor: I have a soft spot in my heart for sailboat racing, so I was justifiably excited when skipper Ken Read (now North Sails’ president) invited me, as a journalist, to sail with the team aboard Avanti, Puma Ocean Racing’s training platform, for an offshore trip ahead of the 2008/2009 Volvo Ocean Race. Under its former ABN Amro II livery, Avanti owned the (then) 24-hour distance record for monohulls (562.96 nautical miles), so there was no question it was blisteringly fast. Stepping belowdecks, I saw that all creature comforts had been stripped for performance, as evidenced by its head, which was situated just forward of the mast. (The galley, of course, was just abaft this same stick.)

And it was just that: a toilet surrounded by a shower curtain. The memorable bit? The seatbelt.

Fortunately, modern heads for cruising boats don’t require this safety feature, however heads are available in a variety of designs and tank options. Here’s a roundup of what’s available on the refit market.

Manual Heads

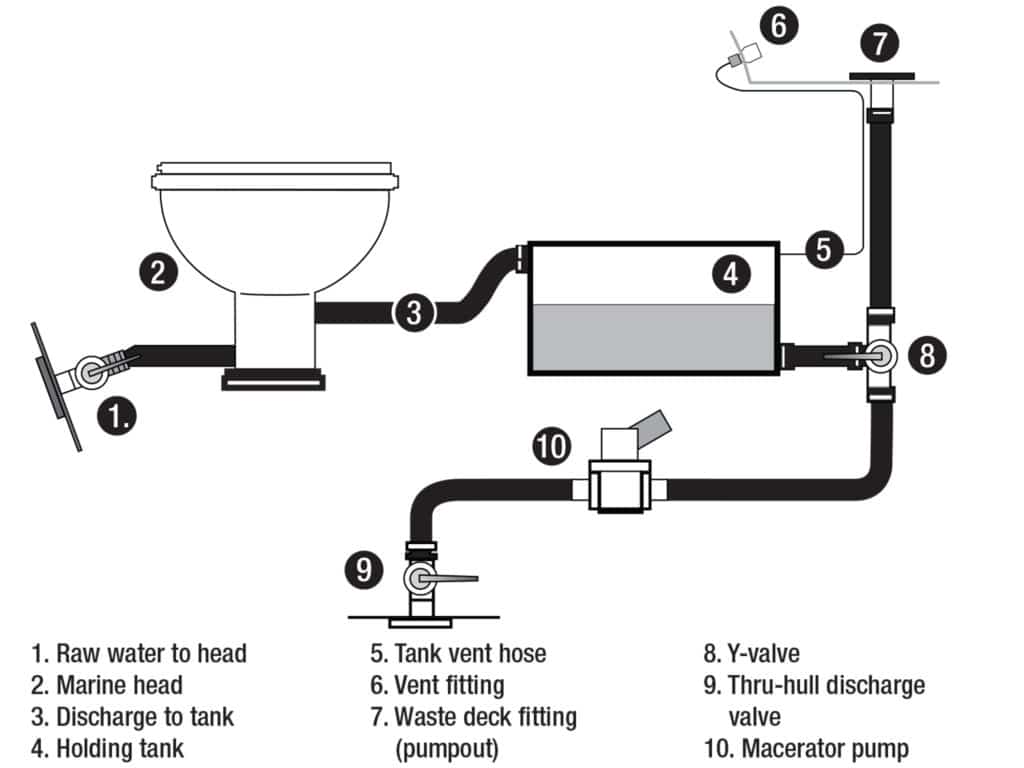

Operating a manual marine head is one of the most important lessons any landlubber heading to sea needs to learn. At its basic form, a manually operated head consists of a toilet bowl and pedestal, the system’s various valves and hoses, and a holding tank (or tanks) designed to be pumped out via a deck-mounted fitting. To operate, users pump a small amount of water into the bowl, complete their business as normal, and then flush by first flipping a selector switch (typically mounted by the pump), and pumping the handle to drain the bowl. Next, the switch is flipped back, and the sailor continues pumping water through the bowl (system depending, 15 pumps is usually sufficient) to flush the lines.

The water being pumped can be either fresh, salt or a mixture of the two. The mission is then completed by flipping the switch once again and pumping the bowl dry. This also ensures that water can’t continue entering the bowl on its own.

When selecting any of the systems mentioned in this article (with the exception of composting heads) for a refit project, users are highly encouraged to overspec their valves and hoses. “It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that the smaller the area you try to push anything through, the more likely it is to clog,” says Kim Carrell, Raritan’s controller of sales and marketing. While macerators

can help alleviate clogs, especially at the aptly named joker valve, landlubbers should be politely reminded of what should—and should not—enter a marine sanitation device (“MSD” refers to the vessel’s entire sanitation system, not just the toilet itself).

“One of the most entertaining don’ts that we hear is the type of toilet paper that gets used or, in many cases, not used,” Carrell says. “It seems there are a fair number of people who put toilet paper in a separate trash can. We test all of our toilets with the most popular brands of toilet paper, and they pass American National Standards Institute requirements.” Still, “headmares” can be borne of carelessness. “Feminine-hygiene products seem to be one of the worst nightmares, largely because the strings get wrapped around the macerator, rendering it useless,” Carrell says. “In most, using a plunger isn’t a good idea because you ultimately will reverse a joker valve or some other component.”

While the potential for clogging is real, manual heads offer some advantages over other systems in that they are just that: manual. This means that they can still operate with low or no power, and they are fairly simple mechanical systems that can be (and regularly are) field-repaired, provided that the skipper carries spares. It also means that these systems typically have smaller price tags than the fancier sanitation systems, which is also an important consideration. Finally, research and test-flight the different pumping options; some people find certain pump designs (such as foot pedals or back-and-forth handles) easier to use than up-and-down mechanisms.

Electric Heads

As the name implies, electric heads replace manual, pump-action flushing and instead employ a user-friendly push-button system. Also, as mentioned previously, electric heads typically include a macerator that functions in a way that’s similar to a kitchen garbage disposal. The macerators can help to reduce the chances of a clog.

As with an at-home garbage disposal, having access to the macerator’s innards is optimum because blades can fail or, as mentioned, unintended objects can become entangled. Owners are advised to ensure that their macerator blades are of good quality, and to look for designs that give direct access to this potential weak link.

One upgrade option, depending on the design of your current head, is to swap out a manual unit for a similar electric one, which can save a lot of DIY time. Another option, which also depends on the age, condition and design of the existing head, is to retro-add a small electric pump. While this doesn’t add a macerator to the equation, it can greatly simplify operations.

Interestingly, the inverse also sometimes works. “We’re unique in that one of our manual toilets is available with electric operation—but not maceration—and it can be easily converted to manual operation if there is a problem with electric,” Carrell says.

Power consumption and loss of power are, of course, considerations for anyone cruising long distances or on especially lightning-prone waters. While each marine head has different power requirements, typically speaking, most are low-draw systems that are punctuated by brief load bursts of 20 to 30 amps, so careful mariners will ensure that each electric head is installed on its own breaker. Also, some consideration should be given to what happens in the event of a power outage. Larger cruising yachts will likely have multiple heads, so one strategy could be to sail with at least one manual head. Alternatively, buckets are time-honored analog workarounds.

It’s worth noting that while marine-head technology tends to be relatively static compared to, say, electronics innovations, there have been some advances, including sanitation systems that use combinations of both fresh water and brine, as well as those that use radio frequencies. “Our latest Bluetooth smart control allows settings of timing and other parameters on a smartphone, and also collects and displays motor data for troubleshooting,” Carrell says.

Vacuum Heads

No, “vacuum heads” isn’t an obscure reference to Phish fans (Google it—it’s real), but rather a style of head that uses a vacuum flush—rather than a hand pump or electric pump—to empty the bowl’s contents. While designs vary, most vacuums systems include a toilet, a vacuum generator (the vacuum pump and vacuum reservoir), a waste tank (including dockside and overboard discharges) and the various tubing, which can make for a sizable installation. Fortunately for owners of smaller steeds, some systems manage to fit all the components into a single, space-conscious unit.

Flushing operations vary among vacuum heads, with some systems relying on foot-activated levers, while others employ the closing action of the toilet seat’s sealing lid to trigger the flush. Either way, vacuum systems work by creating and maintaining vacuum pressure throughout the system. This energy is released when the system is flushed, instantly clearing the contents of the toilet bowl using fresh water. Depending on the system, some can move waste at a pace of 7 feet per second.

Flushing causes the system’s electric vacuum pump to switch on and run until proper vacuum pressure has been restored. The amount of time required to repressurize the system depends on the length of its run from the toilet bowl to the holding tank, but, generally speaking, a minute does the job.

Flushing operations vary among vacuum heads, with some systems relying on foot-activated levers, while others employ the closing action of the toilet seat’s sealing lid to trigger the flush. Either way, vacuum systems work by creating and maintaining vacuum pressure throughout the system. This energy is released when the system is flushed, instantly clearing the contents of the toilet bowl using fresh water. Depending on the system, some can move waste at a pace of 7 feet per second.

Flushing causes the system’s electric vacuum pump to switch on and run until proper vacuum pressure has been restored. The amount of time required to repressurize the system depends on the length of its run from the toilet bowl to the holding tank, but, generally speaking, a minute does the job.

But for cruisers who are seeking a user-friendly low-odor system, and have sufficient space, amp hours and freshwater supplies, replacing a tired mechanical system with a new vacuum-based marine head can be a wise upgrade.

Composting Heads

If you’ve ever visited a backcountry outhouse while hiking, you’re likely familiar with its (sometimes) horrors. Fortunately, marine composting heads such as Air Head and Nature’s Head use clever engineering and some basic chemistry, rather than a hole above a hole, to curtail smell while also helping to lower one’s environmental wake.

The design is basic—simple toilet leads to two chambers: one for liquids, and the other for solids (it’s critical that these are bifurcated). Liquid waste can either be dumped overboard if one is sailing more than 3 miles offshore, or it can be stored in the head or in a separate container. (Another option involves evaporation, but this typically requires significant electrical input and is temperature- and humidity-dependent.) Solid waste is stored in a separate chamber that’s first fed with wetted and crumbled peat moss, which can be supplemented as needed. Over time, this chamber heats up to between 140 degrees and 160 degrees Fahrenheit (ballpark), which is hot enough to kill dangerous bacteria.

After using the composting toilet, a crewmember cranks on a handle-type agitator that mixes the solid waste with the chambered peat moss to kick-start the compositing process. A low-voltage fan circulates air in the chamber and helps to keep the compost dry, further bolstering decomposition.

Once the composting process is complete, users are left with an odorless black powder that’s free of dangerous contaminates or bacteria. Legally, it must be brought ashore and disposed of (it’s great for fertilizing flowers and shrubs but not tomatoes or lettuce).

While marine composting heads potentially present a certain gross-out factor for the non-initiated, they come with several significant advantages, starting with the fact that these green-generation systems don’t require through-hull apertures. Furthermore, marine composting heads aren’t reliant on complicated mechanical systems, joker valves or holding tanks, meaning that they’re significantly less likely to clog or require emergency at-sea surgery (cue the Purell).

Marine-composting heads also allow users to skip the pump-out station; however, prospective buyers are gently advised to research how much “user involvement” is required throughout the composting process, and to ensure that this is copasetic with their notions of happy cruising.

In addition to occasionally writing about marine gear, David Schmidt is CW’s electronics editor.

Vendor Information

Air Head: airheadtoilet.com; from $1,030

Dometic: dometic.com; from $300 to $1,500

Jabsco: xylem.com; from $210 to $1,100

Nature’s Head: natures head.net; from $960

Purell: purell.com; from $1

Raritan: raritaneng.com; from $550 to $2,500

Thetford: thetford.com; from $210 to $12,000

Head Check

If you’re a sailor, you’re likely familiar with a certain and rampantly ubiquitous rotten-egg smell that’s commonly associated with marine toilets and their hoses. Despite the temptation to blame the obvious, these odors have nothing to do with the human condition. Fortunately, the fix is easy and doesn’t use environmentally caustic chemicals. “That smell comes from organisms living in the water that die,” Raritan’s Kim Carrell says. “This can be helped by flushing the system with fresh water before leaving the boat, but it’s important to note that the fresh water needs to get into the bowl and all the lines.”

Should odors persist beyond a few solid freshwater rinses, it’s time to dig deeper. “Always consider the age and condition of the existing hose and tanks,” Carrell advises. “We tell people to take a hot rag and rub it on the hose or tank, and if the odor transfers, then this equipment should be replaced.”

Speaking of smells and caustic substances, Carrell warns about the dangers of using at-home products in marine sanitation systems. “A major cause of early head failure is use of common household cleaners,” Carrell says. “Chemicals in these cleaners can attack most plastics and rubber parts.” Instead, cruisers should look for marine-specific products that won’t harm their systems or the fragile marine environment.