Ever since we cruised from Acapulco, Mexico, to Bay of Islands, New Zealand, in 1988 on Freelance, our 28-foot Bristol Channel Cutter, my wife, Harriet, and I longed to return to the South Pacific. In spring 2021, while going through a closet full of stuff in our condo, out slid a box of old paper charts from our voyage. A large chart of Bora Bora unfolded in my hands. The perfect circle of reef, the lagoon of dazzling blue, clouds streaming like cotton from the island’s volcanic peaks—the South Pacific had enchanted us again.

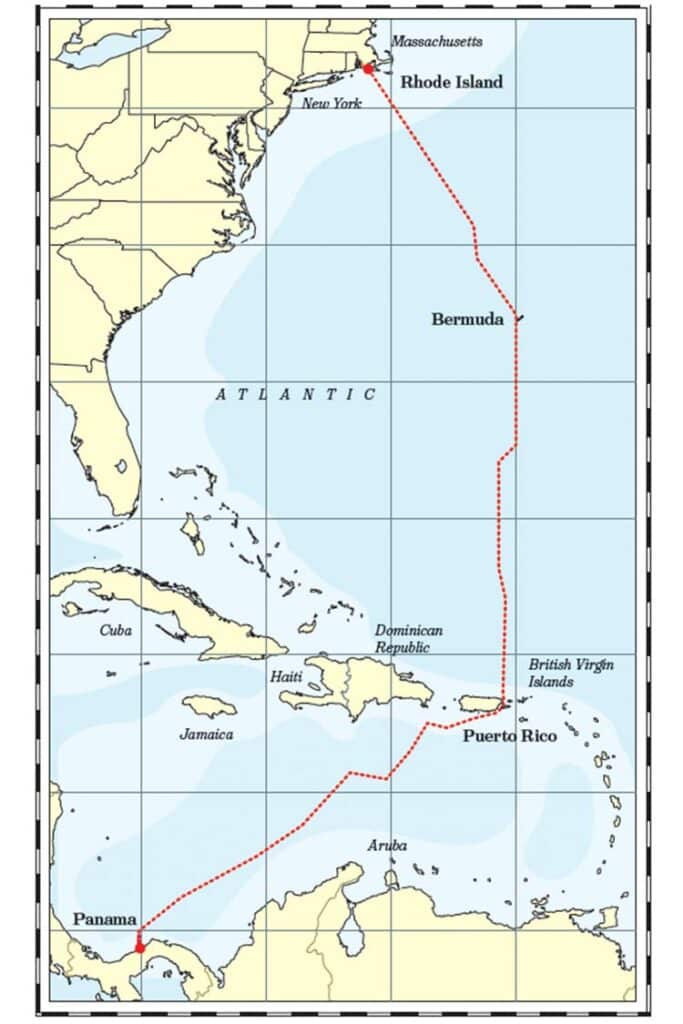

We sketched a plan: From our home port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, we’d head to Bermuda, then Puerto Rico, then the Panama Canal, the Galapagos, French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, the Kingdom of Tonga, and Fiji. We’d arrive in New Zealand a year later. It would be about 10,300 nautical miles, most of it downwind in the northeast and southeast trade winds.

Ocean, our Dolphin 460 cat, had recently undergone an extensive refit and was up to the task. So, off we went.

Massachusetts to Bermuda

Bermuda is an old friend for us. During the 13 years we operated our Caribbean child-literacy nonprofit, Hands Across the Sea, we called into the island 22 times. But getting to Bermuda from the US Eastern Seaboard in the fall is tricky.

First, we looked for the tailwinds of a departing front to launch us off the continental shelf. Next, we looked for the Gulf Stream to quiet down. Finally, we looked for a favorable slant to get us into Bermuda after a three- to four-day hop.

Powerful autumn and early winter gales can be dangerous, so we checked and double-checked the forecasts (we find PredictWind helpful, and we rely on meteorologists at Commanders’ Weather to determine a weather window). We also had an old friend, Capt. Bill Truesdale, join us. Bill is a circumnavigator, and is cool, calm, and able to diagnose and fix anything.

With breezy winds abaft the beam, we made great time on Day One. Ocean pushed through chunky, confused seas, flying a full main and the code zero. But after dinner, I felt seasick. Really seasick. Nine times over-the-rail seasick. Bill, who rarely gets seasick, felt similarly ill. He stood his watch, and Harriet held down the fort.

In the morning, we decided we’d been pushing the boat too hard, sailing too fast for the sea state. Plus, I had started out the passage on four cups of coffee and not much breakfast; my stomach never had a chance. We knew all this was wrong, but we’d been away from passagemaking for a year and a half, and we’d forgotten. Lessons relearned: Ditch the coffee, eat enough noncombustible food to head off the stomach growlies, and take our foot off the gas until we get our sea legs.

The final two days into Bermuda were smooth and fast, pulled along by the code zero.

Bermuda to Puerto Rico

Commanders’ Weather advised us that in a couple of days, a massive system would move south and overspread Bermuda, slamming shut the weather window to Puerto Rico. The choice was to leave the next day, or hunker down for weeks with uncertain prospects. We quickly wrapped up some engine maintenance, saw Bill off to the airport, and hoisted the main for Fajardo, Puerto Rico.

Harriet and I had both been looking forward to getting south, into the tropics and the soft, warm trade winds. It is certainly possible, however, that our hiatus from passagemaking had turned us into softies. Chunky seas bounced us. We slowed down Ocean enough to keep our stomachs calm, and to keep the off watch rested. Our sailhandling skills—reefing the main in the dark, rolling up the code zero before squalls—were a bit ragged, and we revisited our teamwork. We felt more tired than usual.

We’d been pushing the boat too hard, sailing too fast for the sea state. We’d been away from passagemaking for a year and a half. We’d forgotten.

On Day Five, the profile of Puerto Rico rose in the dawn light. We’d been there before only for connecting flights between the United States and British Virgin Islands, so everything about the island surprised us, mostly in a good way. Puerto Rico is larger than we realized, more developed (with malls that have US big-box stores and franchises), and uniformly welcoming to visitors. The shores are ringed with high-end marinas—we spent two nights at what’s now Safe Harbor Puerto Del Rey, the Caribbean’s largest marina—and the island has luxury housing developments, along with funky settlements behind barrier mangroves, and more.

We spent 10 days exploring from the Spanish Virgin Islands to the sheltered south coast of the main island. Nature preserves have kept Puerto Rico’s cruising grounds in good shape, with lots of hidey-hole mangrove anchorages, plus some bioluminescent coves. On holidays, anchorages are crowded with raft-ups of local sport-fishing boats and personal watercraft.

Puerto Rico to Panama

Finally, an entire passage in the trade winds. The course from Boquerón, Puerto Rico, to the entry breakwater at Panama is nearly dead downwind, so we jibed to take advantage of shifts in wind direction and to avoid the near-permanent low-pressure system (possible winds to 35 knots with steep, ugly current-against-the-wind seas) that lurks off the northwest coast of Colombia.

Our sail-carrying plan called for a single reef in the main, and Ocean’s 95 percent overlap jib (roller-reefable) and furling code zero (nonreefable) to suit the daily variation in wind strength. But just a couple of days out, we concluded that we’d idealized the trade winds just a wee bit. “I can’t recall seeing so many squalls like this,” Harriet said. “Maybe on the passage from Fernando de Noronha, in Brazil.”

On Day Three, powerful squall clouds—to the south, west and north—triangulated on Ocean. Each announced itself with alarming gusts, and followed up with sheets of rain just short of a whiteout. We had little choice but to reef down or furl up. We’d peer out at the rain, then turn the ignition key and trundle along behind the squall in weak, ascending air and leftover chop. The squalls meant sailhandling work and slower progress—and nighttime squalls seemed worse in every way.

One evening, a prolonged 25-plus-knot blast sent us surfing down a steep sea at 18 knots. The autopilot steered blithely onward. (Ocean’s hull has lots of buoyancy forward, and a cat’s twin hulls are not prone to broaching, as a monohull might.) But the brief thrill ride through the darkness freaked us out. We double-reefed the main—we were happy averaging 8 to 9 knots—and concluded that we needed a better sail strategy for running deep in intensified trades.

Later, we talked to a cat crew on the same passage who had used only a reefed jib. Their mainsail stayed in the lazy bag. We needed to keep reminding ourselves that, even though we are ex-racers, we were not in a race. We love fast passages, but quality off-watch rest for our doublehanded crew was the top priority.

When we pulled in the second reef, we disturbed a red-footed booby that had taken up residence on our solar panels; the bird squawked, moved to the tip of the port bow, tucked its beak into its wing, and continued sleeping. Later, we found a small black bird, maybe a petrel, snoozing on the dinghy davits. Later still, a flying fish flew into our dinghy. All of it seemed to say: “You are in the trade winds and you are a part of the trade winds, so pull up your socks. Enjoy.”

Some evenings, of course, were astoundingly beautiful, an impossible canopy of stars arcing across the horizon. “There’s the Southern Cross!” Harriet exclaimed, pointing out her favorite.

Nearing Panama, the trade winds mellowed out: 15 knots, 20 in squalls, and far fewer of them. The seas grew smaller and kinder. These were more like the trades we remembered.

By the time we jibed into the inbound lane of the ship-traffic separation scheme for the Panama Canal, I’d finished David McCullough’s 700-page The Path Between the Seas, so I was already in awe of the place. Unfortunately, we were stuck on the Caribbean side for three weeks because of issues with our mainsail batten pocket ends and steering cylinders (Ocean has hydraulic steering). We tied up in Shelter Bay Marina, at the Caribbean entrance to the canal, and the marina’s shipment wizard wrangled our repair materials for us. All the help we needed—a sailmaker and hydraulic guys—was on hand.

After several weeks of work, Karen and Paul Prioleau, cruisers we’d met back in 1988, flew in to join us as line handlers for the canal transit. We also had a required Panama Canal Authority pilot and a specified line handler, who between them had more than 2,000 canal transits. So the 10-hour transit was easy. These 47 miles were a milestone and the gateway to a new life for Harriet, me, and Ocean.

By the time 26 million gallons drained from the Miraflores locks, the final southbound lock, lowering us 27 feet to sea level, and we motored around the bend and under the final bridge, we saw a thin blue horizon waiting ahead: the Pacific.

After 20 years of dinghy racing, the siren song of bluewater cruising called Tom Linskey, aka TL. In the ’80s, he built a 28-foot Bristol Channel Cutter in his backyard from a hull-and-deck kit, and sailed with his wife, Harriet, from Southern California to Mexico, French Polynesia, New Zealand, and Japan. Together, they’ve covered more than 50,000 doublehanded miles, most recently in their Dolphin 460 catamaran, Ocean.