Although I grew up in a sailing-obsessed household with a physicist father who was an early and enthusiastic convert to electronic navigation, my first time experiencing a truly state-of-the-art navigation system was in 2007, when I was invited aboard Puma Ocean Racing’s Volvo Open 70 Avanti to document the team’s offshore training ahead of the 2008-2009 Volvo Ocean Race.

The great Mark Rudiger was navigating, first threading us under New York City’s Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and then into the open Atlantic before our bow unexpectedly and dangerously began delaminating, necessitating a retreat back to the Big Apple, up the East River to Long Island Sound and, eventually, to Newport, Rhode Island. Rudiger masterfully leveraged the boat’s electronics, which included tablets, laser range finders, weather-routing software, state-of-the-art radar, a satellite-communications system and a bevy of belowdecks computers and instrumentation to facilitate this improbable passage.

As gobsmacked as I was by Avanti’s navigation systems and electronics, I’m equally astonished that now, a decade later, even higher levels of navigational precision, situational awareness and electronic sophistication are available to sailors at prices that won’t crush the cruising kitty. Here’s a look at some of the latest features in navigation and marine electronics, broken down by equipment category.

AIS

When automatic identification system technology was first introduced to recreational mariners in 2008, its primary purpose was helping to avoid boat-to-boat collisions while enabling captains to directly hail another ship via its nine-digit Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) number, which is specific to a particular vessel. There are two kinds of AIS: Class A is typically required on commercial boats and ships over 65 feet, and Class B is intended for smaller recreational vessels. (Additionally, there are two kinds of Class B systems: the 5-watt Class B-SO and the 2-watt Class B-CS. For comparison, Class A units broadcast at 12.5 watts.) Given the system’s widespread adoption, the U.S. Coast Guard now uses AIS to mark virtual and synthetic aids to navigation on electronic charts, and — thanks to AIS’s ability to deliver updateable messages to a vessel’s chart plotter — to share localized and germane application-specific messages, which can include updated Broadcast Notices to Mariners or information about shipping-lane adjustments, for example, to protect whale pods. Moreover, there are two types of AIS devices available to sailors: “listen-only” receivers and transponders, which transmit your vessel’s navigation information and collect AIS data from nearby marine traffic.

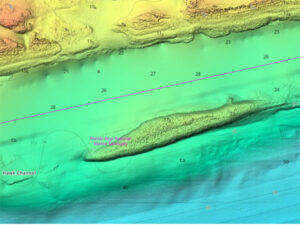

Cartography

Electronic cartography has evolved significantly since Navionics’ founder, Giuseppe Carnevali, unveiled the recreational-marine market’s first electronic chart display, the Geonav, in 1984, but the basic premise remains unchanged. A chart plotter, computer or mobile device displays a raster or vector chart on its screen and uses a networked (or internal) GPS to drop a pin on the vessel’s location. What have changed, however, are the kinds of information that charts contain and the details that are overlaid atop bathymetric data.

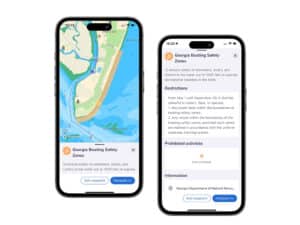

Electronic charts fall into two categories. Raster charts are essentially scanned paper charts. Vector cartography is computer-built and can include both official and user-generated bathymetry information and points of interest, and they can be overlaid with AIS, radar, weather and other types of information. Some modern cartography can also perform auto-routing calculations to determine your safest routing to port B, and chart updates are easier to tackle thanks to Wi-Fi and cellular connections. Finally, cartography companies have created accurate and easy-to-use mobile device-based navigation apps, giving coastal cruisers serious redundancy.

Chart Plotters

Carnevali’s Geonav chart plotter, as mentioned earlier, came online in 1984. It was a (relatively) crude system that used bare-bones graphics to represent location, surroundings and boat. Today’s chart plotters, by comparison, are graphically rich marinized computers that use a wide variety of interfaces that can include touchscreens, keyboards, a rotary dial, a mouse or even a paired cellphone or tablet. Additionally, most contemporary chart plotters employ optically bonded screens, which help to reduce screen fogging, and which can easily be read from different angles, even in direct sunlight.

The other big change to plotters in recent years has been a move to integrate numerous capabilities that were formerly tackled by peripheral devices. These include sounders, Wi-Fi routers or autopilot control heads. These essentially turn the chart plotter into a multifunction display, which can in turn be networked with third-party instrumentation, including AIS, radars or thermal-imaging cameras. Finally, contemporary plotters feature intuitive and user-friendly interfaces that resemble those found aboard today’s mobile devices.

Additionally, B&G, Garmin and Raymarine have each recently added sailing-specific features to their chart plotter operating systems. Depending on the brand, these new features include starting-line assistants for racing sailors, as well as wind-rose tools and graphical assistants that help you determine the best time to tack in order to reduce your estimated time to arrival. While some of these features are aimed at racing sailors, cruising sailors can certainly leverage these new capabilities too in order to make passagemaking more efficient.

Communications

Onboard communications is another segment of marine navigation that has evolved significantly in the past decade, ranging from now ubiquitous smartphones and satellite phones to satellite-communication domes and next-generation flat-panel satellite communications systems that are just coming online.

In between these extremes are long-range cellular and Wi-Fi boosters that allow you to tap into onshore networks from a few miles out, as well as satellite communicators that allow you to transmit and receive information such as email via transmissions composed of small data packets that, while not as fast as a full-scale satellite-communications system, cost considerably less, both in terms of equipment and airtime costs. Critically, the physical satellite networks that support this technology have been significantly upgraded and now offer speeds that, while sluggish compared to land-based connections, are blazing fast compared to previous offerings. Depending on the system, mariners can use this equipment to make voice calls, access the internet or, perhaps most important, download up-to-date weather GRIB files.

Finally, the humble VHF radio has also seen (relatively) recently added features such as digital selective calling for emergency situations, while some more advanced fixed-mount VHFs now also feature built-in AIS capabilities, which can be a great way of adding situational awareness without upgrading your chart plotter or adding a dedicated piece of instrumentation. Also, because AIS uses vessel-specific MMSI numbers, AIS-enabled VHF radios also make it easy to hail other nearby vessels should a potentially sketchy crossing situation begin unfurling.

Heading Sensors

Electronic fluxgate compasses have provided mariners with accurate heading information since the 1930s, but they typically deliver a 1 Hz, or once-per-second, reporting rate that can make for squirrelly rides aboard some boats when reaching or running in a following sea with the autopilot driving.

Fortunately, advances in the aerospace industry have delivered miniaturized and commoditized attitude and heading reference system sensors, allowing marine-electronics manufacturers to build solid-state nine-axis compasses that are accurate to 1 or 2 degrees and boast update rates of 10 to 30 (or more) Hz. This accuracy and reporting rate surpasses any purely mechanical system afloat, though excellent hybrid mechanical-solid-state compasses do exist. This new breed of sensors allows modern autopilots to steer far more accurate courses, and provides some with the ability to self-calibrate or self-learn a vessel’s characteristics while underway. Better still, these black-box compasses are easily networked into a boat’s navigation system via NMEA connections to bolster the accuracy of other electronics and features that require heading-sensor data.

Radar

While magnetron-based radar systems helped win World War II and have aided myriad sailors and aviators since the system’s debut in 1940, marine-electronics companies today are rapidly moving to solid-state radars that use gallium nitride power amplifiers, which broadcast their signals on X-band frequencies (9.3 to 9.5 GHz) using pulse-compression schemes that enable Doppler processing. That is, these new radars use less power, and Doppler processing allows them to identify and assess targets that may or may not become threats. Vessels traveling on a collision course will typically be painted one color (often red); nonthreatening targets are painted a different color (such as green); and stationary objects and landmasses are usually presented as standard radar imagery, giving operators at-a-glance situational awareness. This awareness is further enhanced by features such as automatic radar plotting aid and mini-automatic radar plotting aid, which automatically or manually track vessels, giving a skipper real-time speed, bearing and closest-point-of-approach information. Best yet, gallium nitride power amplifiers are now less expensive to manufacture than magnetrons, representing a rare case of newer and significantly better technology costing the same or less than previous-generation equipment.

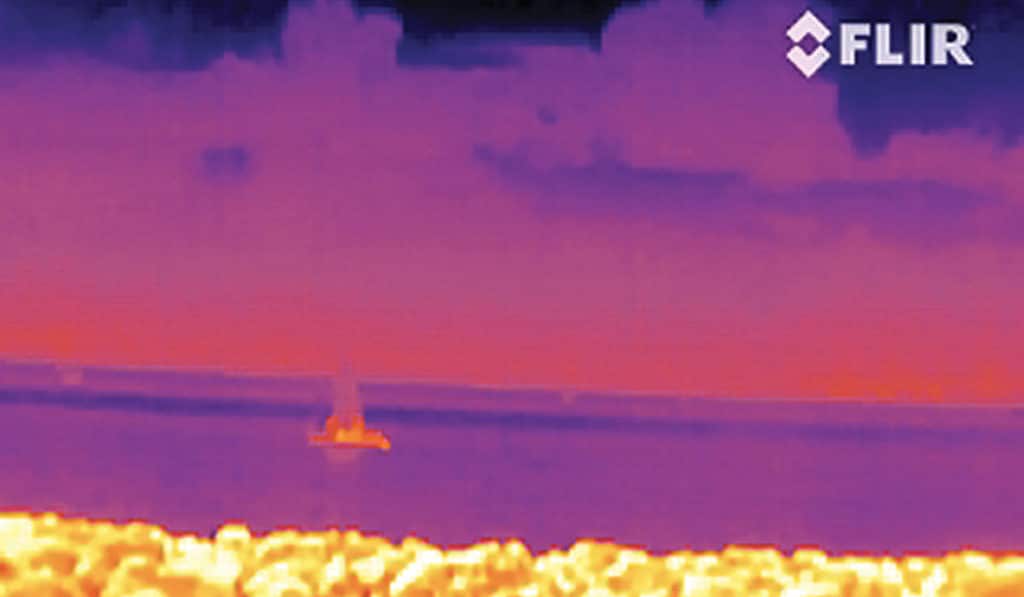

Thermal-Imaging Cameras

When it comes to nav-station cool, it’s tough to top thermal-imaging cameras, which use highly sensitive microbolometer sensors to detect minute thermal differences (one-twentieth of a degree Celsius) between an object and its surroundings. These highly capable cameras are equally adept in the glaring noonday sun as they are during the graveyard watch, and they are available in either handheld or fixed-mount models, the latter of which are controlled by a networked chart plotter and can typically pan and tilt. The vast majority of thermal-imaging cameras for marine use also offer the ability to zoom, but just as with digital photography, optical zooms provide far better image resolution than their digital counterparts.

Virtually all thermal-imaging cameras offer a variety of color palettes, which are useful in different atmospheric conditions and for spotting different things. Some systems even can detect, assess and track targets. Historically, thermal imagers were the trappings of large poweryachts. However, this is rapidly changing thanks to the plummeting prices of both handheld and fixed-mount cameras.

Weather-Routing Software

One of the most dramatic impacts that today’s information age has had on cruisers is the ability to take high-resolution weather GRIB files and import them into computer-based weather-routing software. There are multiple products available, so you should be able to find software that’s compatible with Linux, Windows or iOS platforms. These weather routers use a sailboat’s polars, or performance-characteristic metrics, to determine the safest and most efficient course to your next destination, using user-selected parameters such as maximum (or minimum) forecast wind speeds or wave heights, both of which can affect crew comfort. Weather-routing software can also be used to consider tide and current information, allowing users to play with their optimal departure times in order to make landfall at, say, first light or during a particular tide cycle, when draft might be critical. As with all forecast-based decision making — whether done by skipper or machine — the more up-to-date the data, the higher the chances that its forecast outcome will be accurate, so while cruisers can download a GRIB file before setting sail, they will likely be far better served if they can download fresh GRIB files en route (see “Communications,” above).

Wireless Connectivity

One of the more useful recent evolutions in chart plotter technology has been the now-universal adoption of built-in Wi-Fi connectivity, allowing users to share networked instrumentation and NMEA data with third-party devices such as smartphones or tablets.

That fancy tablet that Rudiger had aboard Avanti? Assuming you have a Wi-Fi-enabled plotter (or an onboard wireless local area network), you can have access to the same on-deck situational awareness that he enjoyed for the price of an iPad, a navigation app and a waterproof case. In other words, for pennies on the dollar compared to Rudiger’s kit.

This same wireless flexibility allows users to fully leverage wearable technology, such as sailing-specific watches and eyeglass-style head-up displays, while also allowing any smartphone or tablet to stand double watch as a chart plotter repeater, the latter of which saves the expense of having to spec extra chart plotters, say, for the helm or nav station below. Additionally, some manufacturers are now offering Wi-Fi-enabled radars that swap their hard-wired data cable in favor of a wireless connection with a plotter or smart device, a technology that also helps reduce weight aloft.

What’s Old Is New

GPS enables ultraprecise navigation. However, the system relies on satellites that are vulnerable to attack and receivers that can be jammed or spoofed. As a result, the U.S. Navy began re-implementing celestial navigation as part of its officer-training curriculum several years ago. While cruising sailors aren’t likely the targets of state-sanctioned GPS attacks, our receivers use some of the same target-worthy infrastructure that the military employs. Moreover, lightning strikes or other calamities can blind a yacht. Careful navigators, therefore, maintain accurate logbooks and practice dead reckoning, while shrewd skippers carry a sextant and related kit for serious bluewater passages. Additionally, the advent of modern celestial calculators (both stand-alone and app-based) and celestial-navigation software ease the burdens and computations associated with gleaning one’s positions from the heavens.