A huge crowd gathers at the breakwater in Gran Canaria to bid farewell to the yachts. One by one, boats from 26 nationalities file out of Las Palmas marina toward the start line at the north of the Spanish island. Crews dance and cheer, and the music changes from Queen to ABBA as Swedish yacht Dawnbreaker docks out to the blare of an Alpine horn. The two white-haired children at the bow seem awed by the fanfare, but their brother, Alfred, waves furiously from the top of a Jacob’s ladder, looking more than ready to take on the Atlantic.

The Chuck Paine–custom-designed yacht is one of 83 vessels (six of them American) taking part in the 2,700-mile rally to Grenada, which has a stopover in Cape Verde. The direct ARC, which sails to St. Lucia, departs two weeks later.

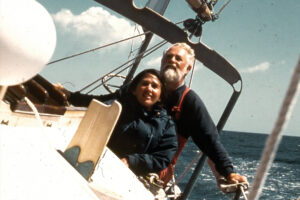

It’s been 40 years since Jimmy Cornell launched the ARC, an event aimed at cruising enthusiasts, not “racing’s elite,” with a focus on safety. Back then, Dawnbreaker skipper Lars Alfredson was navigating with a radio direction finder. Even during his first ARC, in 2003, he was reliant on an SSB radio and a modem to stay in contact.

“You’d spend hours and hours trying to connect, but you got through sometimes,” he recalls. “You see the boats the first day and the last day, and in between it’s just empty sea.”

Now, sailing with his son, daughter-in-law and three grandchildren, Lars has Starlink, enabling the family to run their online retail business at sea.

“I wouldn’t say things are better now, but for the young people who need to be connected all the time and have to report everything that happens, they like it,” says Lars.

At 64 feet, Dawnbreaker is one of the bigger entries in the fleet, with the average yacht being 48 feet. These days, over a third of participants are multihulls, and most are equipped with satcomms, autopilots, solar, lithium batteries and MFDs. But how would the crews feel if they were zapped back in time, Marty McFly–style, to 1986? Would they still do it? This is the question we put to them as they made their final preparations for their big adventure.

Almond angst

“Yes, I’d still go, because I wouldn’t know any different,” says Richard Cropper, skipper of Beneteau 60 Salty Rascal. “You’d just get by with the tools you’ve got.”

The British dad’s decision to embark on a yearlong adventure with wife Louise and sons Jake (9) and Harry (11) was inspired by a Secret Santa gift, a book entitled Sail Away: How to Escape the Rat Race and Live the Dream. Though the idea took hold on Christmas morning 2014, it would be over a decade before that dream became a reality, and only recently did they learn that the gift was from Louise’s sister.

“I think she wanted to get rid of us,” laughs Louise, a primary care physician. “For years afterward, Richard kept saying, ‘Would you do it? Would you do it?’ I only said yes because I never thought we’d go through with it. But I wouldn’t have done it 40 years ago, not without the technology. Everyone back home thinks we’re mad, but they can follow us using the YB tracker, and knowing we’re doing it in an organized group and can send pictures back home normalizes what we’re doing.”

Richard adds: “But the danger of being part of a huge rally is you can’t stop buying stuff. It’s like when you’re at school waiting to do your exams, and everyone’s talking about what they revised, and you’re thinking, ‘God, I didn’t do that.’ You start asking if you’ve got enough equipment. Did you buy enough toilet rolls? We had a panic about almonds, and Louise is like, ‘How many almonds have you actually eaten in the last year?’”

To ease the stress of the passage, the Croppers have hired Brazilian skipper Juan Manuel Ballestero, who made headlines during the pandemic when he sailed three months from Portugal to Argentina in order to see his sick father.

“I was in Porto Santo, and the borders closed. There were no flights, no ferries. I just decided right away, I’m going,” he says. “It was more than a sailing trip, it was an inner trip. I’m still trying to shape it, after all these years, asking myself what really happened. We love our families; that is what COVID taught us. I was going home, and I didn’t care how long it would take.”

Then it was a trip of solitude: a 29-foot yacht packed with 160 cans of food and a bottle of whiskey. This time, Juan’s looking forward to an altogether different experience, as was clear the night of his arrival in Las Palmas, when he was whisked to an ’80s party by a giddy Louise in luminous leggings.

“This family is lots of fun,” he says. “I’m pretty stoked about doing the voyage with the little ones. It will be unique.”

MOB rescue

Hoisting eight flags onto the forestay—an act counted excitedly by a group of boys fishing off the pontoon—is Swan 51 Eira. The monohull is doing the main ARC, and Finnish delivery crew Markus Leppanen and Vilhelm Sjöström are preparing her for the paying passengers.

“Sailing Eira wouldn’t have been much different 40 years ago,” says Vilhelm, tapping the elk-skin-covered wheel. “We have an autopilot now but hand-steer 95% of the time. We have a big racing rudder, which is really responsive, and people participate because they want to steer and sail. They want to learn something new.”

Markus and Vilhelm have tens of thousands of sea miles under their belts. Markus recalls that in the 1993 ARC, they didn’t have a sat phone—just GPS and a plotter. Instead of weather apps, they had a guy navigating onshore, giving instructions over SSB.

Back then they were “just a bunch of friends with the smallest, fastest Swan.” Now, Eira has 85,000 nautical miles on the clock and 15 crossings. She’s a veteran in every sense of the word.

“We use a traditional spinnaker,” says Vilhelm. “At first only in light airs until we know how experienced the crew are. Running it at night requires a bit of practice. The biggest risk is something happens, and the thing that should never happen is a man overboard.”

They reflect on the tragedy in last year’s ARC, where Swedish sailor Dag Eresund, 33, fell overboard from Volvo 70 Ocean Breeze.

“I was routing from Finland,” says Vilhelm. “I noticed all the fastest boats changing course and I knew, hours before it became news, that there was an MOB. It was around 0230, 20–25 knots. When it’s pitch black and a swell of about 6 meters, you know it’s really hard to get someone out of there. These old Whitbread boats don’t turn on a sixpence.”

Eresund was wearing a personal AIS beacon, a safety device that transmits your position to the mothership and nearby vessels, yet sadly he could not be located, reinforcing the fact that even the latest satellite technology is no substitute for lashing yourself to the deck, which people have done since the beginnings of sailing.

Markus recalls an MOB on his 1999 ARC, though happily that had a positive outcome.

“It was a Norwegian racing boat, sponsored by Jägermeister,” he says. “The spinnaker came down in a squall, and they gybed, knocking a crewmember into the water. Even when it’s warm, you’ll only last 24 hours, but here is this guy in a Hawaiian shirt—he takes off his life jacket and places it under his butt to stay out of the water. After 28 hours, a German boat passes and picks him up!”

It’s not the first time a sailor has been rescued by chance during a cruising rally. In ARC+ 2021, British catamaran Coco happened upon a dismasted yacht 140 miles from Grenada and towed it into port, to the relief of the distressed French skipper.

For crews’ safety, it’s a requirement of the ARC that all skippers have the ability to send and receive emails at sea, whether via SSB radio (via a free messaging program called Airmail) or a satcom device such as Iridium Certus 100 or Inmarsat Fleet One.

“We talked about getting Starlink,” says Vilhelm, “but the skipper doesn’t want it because the experience for the crew changes. We have satcomms and can make phone calls and emails, but we don’t want everybody hanging around the cockpit reading the news. You spoil the experience.”

It was during World ARC 2023 when Elon Musk’s low-cost, high-speed internet service took off among long-distance cruisers. While only two of the 20 boats leaving St. Lucia at the start of the rally had Starlink, by the time they’d completed a world circuit six months later, only two boats didn’t have it.

Medical backup

Onboard Frolic, a J/44, we find Rhode Island sailor HL DeVore opening the cava, having successfully Googled a fix for his B&G wind sensor, saving $3,000 in parts and labor. His ex–U.S. Coast Guard vessel is equipped with Starlink, a piece of kit HL wouldn’t sail without.

“I do love the romanticism of not being able to communicate other than with attempts at SSB,” he admits, “and I’m old enough to have sailed in those days, but being connected gives the family at home security, and means we can liaise with a medical team if needed—in fact, the same one used by round-the-world sailor Cole Brauer. We’ve got IV kits, medicines—everything you could possibly need—and with modern comms we have the comfort of knowing we can solve issues at sea.”

Meant to be?

Although Starlink draws a significant amount of power, the benefit of being able to make video calls and stream sports games or Netflix has made today’s cruising yacht a true home from home. It’s allowed Mexican family the Sidauys to sell their home and possessions and move onboard their Lagoon 52F catamaran Ruaj. This new wave of adventurous young families, who buy production catamarans and choose cruising as an alternative lifestyle, was rare in the ’70s, when the majority of ARC participants were older, wealthy couples.

For Gabriel Sidauy, the idea of taking on an Atlantic crossing was sparked during a chance meeting on a flight from Tijuana to Cancun.

“The man next to me was checking out boats and charts,” says Gabriel. “He was about to start this amazing adventure with his wife and three kids. I said to him, ‘That’s the best thing I heard in my life!’”

Gabriel’s children, Moises (now 14) and Natalie (10), loved the idea, but it took four years to persuade his wife, Victoria, to sell up and sail away. When finally she agreed and they shared their plans with neighbors, they were put in touch with a sailor who agreed to be their mentor.

It turned out to be none other than Emanuel—the guy Gabriel met on the plane.

“I told him he changed our lives, and he didn’t remember me,” laughs Gabriel. “But he was great. He told me about the ARC, what boat to look for, and he came several times to the house with his wife to tell us about his experience.”

The Sidauys bought Ruaj in Italy and spent a year sailing around the Mediterranean before making their way south to the Canaries. Thanks to Starlink, Gabriel can run his plastic recycling business at sea, while Natalie and Moises can be homeschooled, with regular calls to classmates and tutors.

“We have learned many things,” says Gabriel. “We used to live in a big house in Cancun with all the space we wanted, and now we learn to live with what is necessary.”

The bare(ish) necessities

One of the joys of the ARC is seeing what families deem “necessary” for their transatlantic, whether that’s a 50-inch TV, washing machine, coffee maker or, in the case of the Sidauys, “aerial silks,” which gymnast Natalie has tied to the forestay.

“Gymnastics is my passion,” she says breathlessly, while twirling and tumbling to the applause of neighboring boats. “I also love the night sky and can’t wait to see shooting stars, and play my ukulele with Moises on his guitar.”

So, a final question: Would they do this 40 years ago?

“No, it would not be possible,” confirms Gabriel, who has to cut short the interview to receive a video conference call.

Without modern tech, Gabriel would still be in Mexico dreaming of a long-ago conversation with a man on the plane. Most likely, the Croppers would be in drizzly Manchester, England, working long hours and doing school runs. Yet for experienced sailors such as Lars Alfredson, who has sailed to the Arctic and Antarctic, and HL DeVore, a navigator with 14 Newport-to-Bermuda races under his belt, waking up in 1986 in the middle of the ocean would pose no problem whatsoever.

The great thing about rallies such as the ARC+ is that these types of sailors can come together and cross the ocean in whatever way suits them, knowing that at the end of it all, in Port Louis Marina, Grenada, they’ll be sharing stories over a rum punch as the sun goes down over the Caribbean Sea.