It was a late-afternoon in March, we were anchored in 15 feet of vivid turquoise water in Union Islands Chatham Bay, 25 miles north of Grenada, and I was wondering how on earth it had happened. This was a very different kind of charter for me. For starters, we were on a catamaran–Hozro, a 37-foot Jeanneau Lagoon. As a dedicated monohull man, I couldnt believe I was sailing the Windward Islands in a cat. But Id wondered for years why catamarans are so popular with Caribbean charterers, and now, at last, I was finding out.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Mike Toy|

| |

|

|

| |

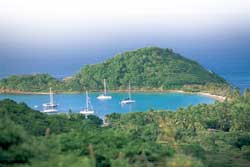

| Maneuvering through a small fleet of cruising boats, like this one at Mayreau, shouldn’t have been too challenging, but in Hozro’s case, the autopilot probably should have been on standby.* * *|

| |

|

|

| We were tucked safely into a bowl of rocky cliffs smothered in the kind of dense, low trees and bushes you find in the Mediterranean, and the warm wind that scooted down over the cliffs brought us sweet whiffs of spicy, resinous vegetation. June, my wife, was laughing, as she always does, at the antics of the brown pelicans fishing near the shoreline, where the rocks are whitewashed with guano. Farther out, small fish jumped, and gannets dove for them. Oblivious to the slaughter around him, a small turtle paddled past our stern, sticking his head up at an odd angle to squint at us. He looked puzzled, but probably no more than I was. This charter was full of things Id normally never do.

For example, the bay in which we were anchored was wide open to the ocean on the western side–a place I wouldnt even consider back home in the Pacific Northwest. Yet its safe; the trade wind always blows offshore here, they say. Intellectually, Im forced to acknowledge the truth of that statement, but physically, I still react with apprehension. And that wasnt all. For the first day of our charter, we had a professional skipper on board. Ive never even dreamed of having such an arrangement.

But I shouldnt be amazed by these things. The Caribbean has always been full of surprises. In 1987, June and I and our 17-year-old son, Kevin, had come angling up the South Atlantic, bound from South Africa for the Windward Islands on a 31-foot sloop called Freelance. We were 16 days out from the tiny island of Fernando de Noronha, off Brazil, and aiming to make landfall on St. Vincent, whose Richmond Peak, with an elevation of 3,524 feet, is visible for 30 miles. A noon sextant sight put us within 12 miles of land, but my eyes told me that we werent. Nothing was on the horizon in any direction.

Suddenly, I noticed a bright flash in the sky up on my right. It was a window high up on a mountainside shining in the sun. St. Vincent suddenly appeared all around us, and I jibed the boat all standing to avoid running aground, although we were still three and a half miles away. A heavy sea haze, which gives no indication of its presence but cuts visibility to less than five miles, had deceived us.

On Hozro, we knew exactly where we were. Fifty yards behind us in Chatham Bay, a three-masted German square-rigger with bright-green sails weighed anchor and was getting under way without an engine, under the inner jib and the fore-topmast staysail. Her acres of canvas wafted her to sea, and her wake lengthened in the sparkling path of the setting sun. June and I watched spellbound.

There’s a romantic streak in most sailors–a hankering to go voyaging–and no better training ground exists than the Windward Islands of the West Indies. The closeness of the islands and the snug nightly harbors offer an opportunity to sample ocean cruising without total commitment. For eight or 10 miles at a time, on passages between islands, you experience the real deep-sea, trade-wind Atlantic, open to the east. But every night, you sleep in a protected

anchorage.

The day before, a Monday, wed started our charter cruise in Grenada, not only because its beautiful but also because its exceedingly friendly, has the biggest airport in the region, and is in a more natural state than some of the bigger islands to the north. Its also close to the Tobago Cays, which Id long wanted to visit.

Jacqui Pascall, an expatriate Brit with a solid sailing background, had persuaded me to try a catamaran. She and her husband, James, own and operate Horizon Yacht Charters (Grenada) Ltd. in True Blue Bay, near Grenadas southwest tip. HYC, with its flagship base in Tortola, B.V.I., and a new base set to open in Antigua in November, is a relatively small operation in Grenada. There, it has a dozen or so boats ranging from 38 to 48 feet, which means you enjoy personal, individual attention. The companys physical location is attached to True Blue Bay Resort, so you walk onto the marina pier from its restaurant-on-stilts.

Jacqui also convinced me to take a skipper for the first days long beat north to the island of Carriacou, which is part of Grenada. Our skipper, Mick Forster, could brief us on local navigation and demonstrate all of the boats systems while we plowed north along the lee side of Grenada. This would save hours of briefings and demonstrations at the marina and give us an early start that amounted to an extra day afloat. Mick, a likable Yorkshireman, quickly became a friend as well as a perceptive advisor.

By late afternoon, Mick had us in Carriacous Tyrrel Bay, a vast and peaceful cove thats surrounded by lumpy volcanic hills and has an easy entrance. We anchored in 10 feet of water and went ashore for a meal of callaloo soup and curried beef. The next morning, we motored around the corner to Sandy Island for a swim. After a dull, gray Pacific Northwest winter, the bright colors of the Caribbean were a sensory assault. The sand was a vivid white, the water was bright turquoise, and the silken caress of the trade wind against bare skin was bliss.

A little farther on was the port of Hillsborough, where Mick showed us how to get outward clearance from Grenada. Grenada and Carriacou arent part of the country known as St. Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG), so we had to get outbound customs clearance from Grenada and inbound clearance for SVG.

The dinghy landing at the Hillsborough pier was guarded by a local entrepreneur whod keep an eye on our boat and outboard for EC$5, about US$2. Mick considered this a wise investment. Customs and immigration procedures are informal to anyone used to dealing with government departments in Europe or the United States, but they go smoothly. A young female customs agent sat singing to radio music while I filled out the various forms and handed over numerous crew lists supplied by Horizon.

Once cleared out of Grenada, we said good-bye to Mick, who caught the ferry back home. We headed for Chatham Bay, eight miles away on Union Island, where those pelicans were diving, and anchored inshore of the German square-rigger with the green sails. We could hardly believe the best was yet to come.

Early the next day, we cautiously motored the few miles to the town of Clifton on Union Island, using our eyes, the GPS, and those wonderful Imray-Iolaire charts to avoid coral reefs off Frigate Island, Grand de Coi, and in Clifton harbor itself. I went ashore in the RIB and tied up at a jetty near an open-air restaurant bordered by brilliant bougainvillea and oleander. I asked a diner the way to customs and immigration. “Just follow the white picket fence,” he said.

Suddenly, I was in the middle of town, where beeping cars and trucks drove around dogs sleeping in the road. I found the customs building, where I handed over money, forms, and passports and was told that the immigration officials were at the airport, up the main road. I found the airport and the immigration officer and knocked politely on his door. After a while, a man appeared, examined my documents, and took them to the immigration officer for his signature. We were cleared into SVG.

Back at the boat, we ate lunch and headed for the Tobago Cays, six miles away. Theyre a national park, accessible only by water, and totally unspoiled, with dancing palm trees fringing beaches of pure white sand and water of unbelievable colors.

We found a solitary place close to the south end of three-mile-long Horseshoe Reef and anchored. We were in eight feet of water as clear as gin when you looked straight down but a vivid turquoise as you looked across its surface, shading into deeper blues and browns where coral grew. At night, the dinghy painters shadow wriggled snakelike on the white bottom in the silvery light of the half-moon.

By day, there was something sensual about the warm wind and the dazzling colors that made you want to rip off your clothes and soak up the sun. Indeed, all around us, on boats and beaches, women were topless. Next door, on a Moorings 413, a naked man showered on the stern. June, rarely bothered by a lack of social conventions, said he looked pretty good. Later, he accidentally dropped a bucket overboard and had to swim for it, which meant another naked freshwater shower. Just showing off, I thought to myself.

After a sound sleep and a lazy breakfast, we took the dinghy ashore to Baradel Island, in the middle of the horseshoe, and ran into New Yorkers Bob and Jenna, from the charter yacht Satyrus, doing the downwind run from St. Vincent to Grenada. Everywhere we anchored, a bumboat hovered in the background, ready to pounce as soon as we were settled. But down here in Grenada and SVG, we found them not as insistent as those in the islands farther north. They provided a service–ice, fresh bread, oysters, you name it–and they’d fetch the request in their brightly colored boats with such names as Let Them Talk, Seasoning, Desperado, Shark Attack, and Never Give Up.

An unpainted aluminum French boat anchored next to us. I hailed them and invited Martine and Bernard Grimaud over for a glass of wine in our spacious saloon. They were middle-aged, semi-retired, and brown and fit. They worked five warm-weather months in France and returned to cruise the rest of the year on their 42-foot sloop, Maeline. Theyd been cruising since 1985, wandering when and where the whim took them.

On Saturday, after two delightful days in the Cays, we decided to clear out of SVG and enter Grenada all in one day. We retraced our course and headed back to Clifton on Union Island. This time, the customs building was chained and padlocked. Damn. Obviously, customs officials didnt work weekends, only Monday through Friday. I asked a man sitting outside when customs was likely to reopen. “Dey at de airport,” he said. “Customs, immigration, everting at de airport today.”

Oh, joy. I treaded up the pockmarked road to the airport, past the pink oleanders and the chain-link fence beside the runway, past the bench with a sign that says, “Every visitor is an honoured guest.” I was the only visitor in the whole airport, and it took about 20 minutes to find the right people, fill in the right forms, and get cleared out of SVG.

From Clifton, we fled downwind eight miles or so to Carriacou, where we anchored in our old spot off Hillsborough. I made my rounds to the police station, then customs and immigration, and finally back to the boat. On the way around to Tyrrel Bay, I had to navigate carefully; the first time, Mick had taken us in, and I hadnt paid much attention.

On Sunday, we hoisted the dinghy into its davits and left Tyrrel Bay early en route to St. Georges, Grenadas capital, about 30 miles down the way. We had a glorious downhill reach in the open sea, and the cat bustled along in 15 to 20 knots of quartering wind. I found it both eerie and exciting that she didnt heel when a puff hit her, instead spurting forward. Little puffs of cloud flew across the hot face of the sun, and white horses reared up astern, but there was no malice in them. The wind was warm, and the spray on deck felt like bathwater.

We passed to port Kick Em Jenny, a nearly 700-foot-high rock island, and ran down the lee of Grenada in calm water, passing pretty little bays with palm trees, white beaches, and, among the dense greenery, the orange-red flashes of flowering immortelle trees. We anchored in the outer harbor of St. Georges and dinghied into the beautiful town thats guarded by ancient forts on the hills, with colorful homes rising in serried ranks behind the natural deepwater harbor. It all seemed very Mediterranean.

The next morning, we motored to windward the last few miles to our marina in True Blue Bay and checked into the hotel. We still had time to explore St. Georges and the islands rugged interior, famous for the rain forest where nutmeg and teak flourish. But for the moment, we were happy to look back on another wonderful sailing adventure in the West Indies. It never lets us down. The only thing that saddened us? We hadnt discovered Grenada earlier.

John Vigor is a sailing writer and editor who sails his 27-foot Cape Dory, Sangoma, out of Bellingham, Washington. He is the author of several boating books, and two more to be released shortly: The Practical Encyclopedia of Boating (International Marine) and Small Boat to Freedom (Lyons Press), the story of his familys voyage from South Africa to the United States in their 31-foot Freelance in 1987.