At 7 a.m. last Monday in Linton, we sat on Ithaka‘s side deck and watched as Frank and Lynda on Simba, anchored beside us for the past week—indeed, here and there for the past few months!—raised their CQR from the velvety thick mud of Linton harbor on the mainland coast of Panama. As the anchor broke the surface, Lynda guided the Alajuela 38’s elegant, varnished tiller, and our friends weaved slowly through the boats. As they passed Sand Dollar, Frank raised the main, and called good luck to Cade and Lisa. Then they ghosted past Albatross, and wished their best to Helmut and Hannah. Next was Street Legal; Guy and Annika were waving good-bye, as were Warren and Robin on Cuchara. Everyone in the little harbor was up and on deck to salute Simba‘s departure for Bocas Del Toro, 170 miles to the west, where the Cassidys planned to leave the boat while they fly home, and then do some inland travel to Costa Rica. We’d been sailing with Simba since they joined Sand Dollar and Ithaka in Providencia, Colombia, back in April. In fact, we’d sailed with them for a while last year, too, in Belize.

| | Historic Portobello, named by Columbus, who took shelter in its large bay, was sacked by Captain Henry Morgan in 1668. * * *| _Simba_ finished her good-bye lap, turned, and over the next hour slowly disappeared behind the islands to the north. We had an SSB radio schedule set up with Frank and Lynda for every night at 9, but other than that, our good friends were retreating from our daily lives. And this wouldnt be our only difficult good-bye here in Linton.

With Simba and Sand Dollar, we’d sailed west along Panama’s rolly coast from Porvenir several days ago, skirting many briar patches of reefs and negotiating an endless procession of stacked 10-foot swells that rocked our boats and our stomachs the entire way. For only the second time since Douglas and I started cruising, I had to pop a Stugeron antiseasickness pill to keep my breakfast down. We stopped at a midpoint anchorage for the night, an indentation on the coast called Escribanos, which turned out to have a hellish entrance. Had we not been in company of two other boats, one of which was already inside the reef when Ithaka arrived outside it, we would’ve taken one look at the seemingly unbroken line of heaving, boiling water, skipped it in sheer dread and sailed onward for Linton despite the hour. But Sand Dollar was in, and there we were.

|

| | photos courtesy of Marty Baker| | We left Porvenir for Escribanos. The runway on Porvenir is notoriously short, and accidents do happen. Here, a plane approaches for a landing, very close to the anchored boats. The second photo shows one plane that, only several months ago, didnt quite stop in time before blasting into the airport mens room. No one was hurt. | | * * *|

We took our customary deep breaths, examined the chart for the 10th time, and pressed in as well, following the bearings recommended by Tom and Nancy Zydler in their thorough book The Panama Guide, A Cruising Guide To The Isthmus Of Panama. Our depth went from 40-something feet to 15 as we crossed through the reef. Then there were coral heads on either side of us, and still the biggish rollers, and finally we surfed inside the reef line. With Douglas halfway up the mast and me at the wheel, by the time we were in, my stomach was in my throat. We anchored Ithaka in mud with only two feet under her, just before a squall hit: zero peace of mind.

| | photo courtesy of Cade Johnson| | Cade went up the mast of Sand Dollar to check his masthead fittings. While he was up there, he snapped this photo of Ithaka. * * *| The next day, we faced the same music going out, but in the opposite direction. Thrilled to be free of the wretched place, we shouldered into the same swell, rolling toward Linton with the wind at our backs. Douglas and I felt immense relief, finally, when we passed around the dramatic islands of Isla Grande and Isla Tambor, massive outcroppings of rock just off the mainland coast, and dropped our anchor in Linton at about 2:00.

“Howzabout we stay here awhile,” I suggested to Douglas, without even knowing what the place had to offer.

“Sure, howzabout forever?” he said, without hesitation. Little did we know then how full the next two weeks would be.

Around us were Simba and Sand Dollar, as well as a few other cruising boats, including our friends on Street Legal, Guy and Annika, who’d arrived the week before. Each would have their own dramas unfold here, starting with Sand Dollar. A few days before, while we were all anchored in the Lemon Cays of the San Blas, Cade and Lisa received an onboard e-mail (via their enviable ham system) from Al and Teresa Jacobs, our teacher friends in La Ceiba, Honduras. Together with the Jacobs, whom we’d met through this website in January, after they e-mailed us about The Log Of Ithaka, we’d shared many good times while Ithaka was hauled out for a paint job at the boatyard. Sand Dollar, a Polaris 43, was being painted the same week. We’d all hung out together, and become fast friends; so much so that Al and Teresa flew from La Ceiba to Guanaja, Honduras, to spend a week with all of us before we set sail for the southwest Caribbean.

| | Many of the stones used to build the vast Portobello fort were removed and used in building the great jetty at Panama City. * * *| Since those days, last spring, lots had happened. Teresa had finished her doctoral dissertationshe was Dr. Jacobs now! and she and Al had been recruited by the prestigious Escuela Bella Vista School in Maracaibo, Venezuela, accepting positions as principal (Teresa) and computer teacher (Al). Now, she e-mailed, Teresa wanted to know if Cade, an engineer, would be interested in teaching. She had an immediate opening for a science and physics teacher in Venezuela. She wanted someone with real-world experience, and she remembered Cade had said hed always dreamed of teaching.

| | The cannons of the Portobello fort still aim to the entrance of the protected bay, flanked on three sides by high hills. * * *| Cade and Lisa rocketed over to _Ithaka_ in their dinghy, called Teresa on our Iridium satphone, and bombarded her with a series of questions. Everything she said made the situation sound better and better. Before the night was through, Lisa and Cade said they really wanted to do it, as theyd hoped to find rewarding work while they were cruising, and refill the kitty as they went. Cade e-mailed his resume to Teresa, and within two days, he was “interviewed” by the superintendent, who apparently liked what he heard. Teresa made the formal offer, and Cade accepted it, all over onboard e-mail and satphone in the remote San Blas Islands.

There was one big hurdle though: The job was to start as soon as possible.

Standing between Sand Dollar and Venezuela was a 650-mile beat against the powerful easterly trade winds, around one of the most treacherous coasts in the Caribbean. But there was more. When Simba, Ithaka and Sand Dollar went to Porvenir to check in officially (having been in Panama at that point for a couple of weeks), Lisa and Cade discovered, horrified, that they’d left all their boat papers and passports in an internet cafe in San Andres, Colombia, one month before! Frantic, they called Cade’s dad in the States and asked him to read their Yahoo e-mail, remembering that that e-mail address had been written on one of the lost documents. Sure enough, a message was waiting for them, sent from the girl in San Andres who’d found their documents; she was still holding onto them.

There’s almost nothing that can match the feeling of exposure in a foreign country than not having your passports and boat papers in order, and since September 11, 2001, getting replacement papers from the United States has become a major ordeal. In the most benign circumstances, were you to be discovered without passports and zarpes, you wouldn’t be allowed to go anywhere until you’d gone to an American Embassy to place an order for replacement papers, or until you’d returned to the United States to deal with it in person. In either of these complicated scenarios, Cade would run out of time and lose the opportunity for this job—plus whatever other major hassles would come his way.

| | For centuries, Portobello was the end point for the Spanish Plate Fleettheir stolen treasures were brought here by mule over the mountains from the Pacific side. * * *|

We all put our heads together in Porvenir, anchored as we were right under the very nose of the customs and immigration offices. Finally, Cade and Lisa decided they would lay low in Porvenir that afternoon, not check in, not report the problem to any authorities, and first thing the next morning boogie on up the coast to Linton with Ithaka and Simba. They knew they had to find someplace in Panama City or Colon where they could get the papers safely Fedexed from the internet cafe in San Andres, a process that would take at least a week. After that, they figured they’d stock up and immediately start the slog to Maracaibo. But to whom could they send these precious papers in the city, and how would we get them from the city to Linton? Douglas and I had one idea, though it seemed a long shot.

An hour or so after anchoring in Linton, and settling the boat, having had a calm-down drink, I heard Douglas gasp, “I don’t believe it! I don’t believe it! It’s Gringo Joe!” The speeding 26-foot (made-from-one-tree) ulu, brightly-painted with “GRINGO JOE” on the bow, sliced through the water about 10 yards from Ithaka. Douglas waved his arms and whistled to get the attention of the two black men and one white one onboard the lancha. They all turned when they heard him. “Joe! It’s Ithaka!” Douglas called out. “Hello there!”

“Ithaka? No way, man. I don’t believe it!” said the big white Kojak of a guy.

“I don’t either!” said Douglas. “Wow! Awright! This is too cool. Come on over!” He’d been corresponding with Joe Logan, aka Gringo Joe, for a year, ever since Joe had sent us an e-mail through the CW website to tell us he’d been following the Log, and offering us some useful technical advice when our old alternator bombed out. Joe had mentioned to Douglas that he was building a little house down here, on Isla Grande, only a mile away, and said he hoped we’d visit, which was in fact one of the reasons we were there. When not building the house, it turns out that Joe lives in Panama City. So began our wonderful in-person friendship with Joe and Cecilia Santamaria Logan. And so ended Sand Dollar ‘s Fedex dilemma.

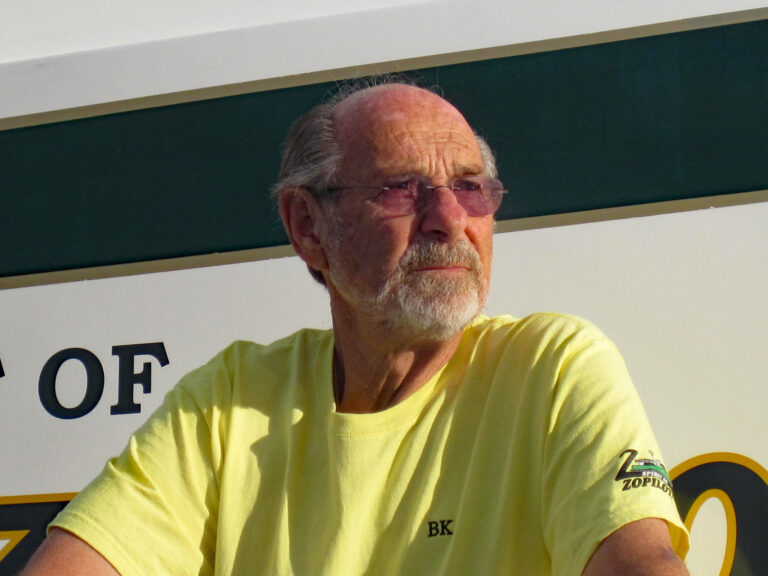

| | Joe and Cecilia Logan * * *| Over the following week and a half, Joe and Cecilia had us all up to their new weekend house, which Joe had spent the past two years building, we had Joe out to _Ithaka_, and the _Gringo Joe lancha_ became a fixture among the cruising boats anchored in Linton. The Logans had a cookout for a bunch of the cruisers in the harbor, and they took Guy, Annika and me into Panama City to accomplish some errands and gave us a royal tour. They showed us the Pedro Miguel Boat Club in the middle of the Panama Canal, and we watched container ships passing through Miraflores Lockan enormous thrill. We drove around new Panama City, a panorama of modern skyscrapers, an impressive Centro Medico area, and up-to-the-minute shopping of every kind you can imagine. Best of all, he and Cecilia introduced us to old Panama City with its antique townhouses, Victorian carved woodwork, cobble-stoned streets, and here and there intimate cafes and galleries tucked in amongst the traditional storefronts. We ate to our hearts content in sophisticated reasonably priced restaurants, something I hadnt done in months, and we all got to know this wonderful larger-than-life character, and his generous, beautiful wife.

| | The Logans hosted a cookout for the cruisers anchored in Linton. * * *|

Joe had lived in Edenton, North Carolina, for 28 years, and had been a pilot for Eastern Airlines, then for Southern Air, until his retirement a few years ago. His wife Cecilia was a banker from Panama City, who’d retired in 1996 from Bank National de Paris. After living in Edenton, they decided to make their permanent home in Panama, where they’ve been since 1998, and loving it. Two years ago, Joe embarked on the project of building a getaway house on Isla Grande, an unspoiled little hive of local waterfront establishments strung along a sandy walking path, all only a two-hour drive from the city and a short lancha ride from the mainland.

Joe and Cecilia showed us the personal side of Panama City, but it’s really little Isla Grande that won our hearts. This is the island where Joe got his nickname. From the start, all the locals referred to him as Gringo Joe, to the extent that deliveries of building supplies destined for “Joe Logan” never made it. No one knew who Joe Logan was. It was only when he gave up and started having deliveries sent to “Gringo Joe” that materials made it to his building site. Finally, he embraced the name and painted it on his lancha.

| | photo courtesy of Marty Baker| | There are no cars on pretty Isla Grande, so kids play freely, and the pace is slow. * * *| Today, with his house on its way to being finished, Joe has become part of the islands fabric. Hes employed lots of local people during the project and worked side by side with them all day every day. He knows the men and their families. Hes in love with the place, and we could see why. Thick green palms and evergreens grow wild and tall throughout the interior, home to millions of songbirds. A pretty beach fringes the island, and the views are spectacular. Along the sand path that connects the houses with the occasional _tienda_ or little restaurant, parents let their children play freely, with no worries about carsbecause there arent any. There are a few inns for tourists, and terrific diving nearby, but the place is sleepy, undiscovered, and out of the way. We loved it, and dinghied there every chance we gotto grab a cheap bite at one of the excellent little eateries, to visit Joe, and to hear his stories. He became the great pleasure in being there.

“When I was a kid,” he said, “every Sunday, I watched my father iron five shirts, one for every day of the week. He was a teacher, and he always looked so damn happy when he was ironing. Whaddya so happy about anyway? I said to him once.

“I like teaching school, he said. I just look forward to going to work. That impressed me. I wanted that feeling, and I got it when I became a pilot. I just loved going to work every day. And now I love this, being here, being part of this place.”

| | Budding schoolteacher Cade Johnson* * *| This place, as Joe put it, is easy to get hooked on. One day, Cade, Lisa, Douglas, and I set out to walk up to the lighthouse that overlooks Isla Grande, a lighthouse designed by the same Monsieur Eiffel who built the tower in Paris. As we headed out, torrential rains began to drive us back down the hill, to the shelter of the nearest cafe. We sat under the tin roof and drank hot coffee as, all around us, lightning bolts cracked open the earth with their horrendous loud claps. The sound and light show was amazing, and we could see the bolts clearly, one after another. In my life Ive never seen so much rain fall at once.

In front of us in the Isla Grande anchorage were a couple of sailboats bouncing around in the squall; each had seen better days. There was the incongruously named Tara, which was a peeling blue steel, rusting hulk with a toilet mounted on the stern rail; and in equally bad repair was Most Wanted, looking like nobody wanted her. All along the Central American coast are sailboats like this, that end their journeys mid-cruise, then start falling apart in the sun, and you sit and wonder what on earth their stories could be.

| | Throughout Portobello is artwork celebrating the Black Jesus. This one, we thought, also seemed to celebrate Little Richard, but we could be wrong.* * *|

We huddled together, Douglas and Cade talking about teaching, and the best strategies for making Maracaibo, and Lisa and I talking about what it will be like for them to live on land again, and this rain, and how as children we both loved to go out to play in it. Id put on a dress, I told her, get my mothers umbrella, sneak out and do dance numbers on the back of my fathers pickup truck, belting out “Singing In The Rain.”

“Girlfriend, thats the difference between you and me,” laughed Lisa. “I loved playing in the rain, too, but I grew up in Kentucky. When it started to pour, Id put on my bathing suit, grab a piece of cardboard and start sliding down hills into the mud!”

| | Lisa and Bernadette * * *| I was going to miss Lisa something fierce. Wed been sailing on the same track since the beginning of the year. Wed spent Christmas together, shared our secrets, fears, joys, recipes, laughs, and sorrows. Now this new job in Maracaibo, for which we were all very excited, was bringing us to good-bye far sooner than wed planned or wanted. As soon as their documents were delivered to Joes place in the city, which would happen any moment now, _Sand Dollar_ would need to up-anchor and skeddadle. As we talked, the Isla Grande Lighthouse, built of steel, took a direct hit by a lightning bolt!

We spent our days in Linton doing boat projects, exploring, visiting our new and old friends, and provisioning in Colon. One day, we all took the bus to Portobello, only eight miles away and the site of a dramatic Spanish fort built in the late 1590s. Now the town is built in and around the fort, the remains of it are everywhere, open to everyone to amble through. Ancient ramparts stick out of houses, old worn-stone Spanish footbridges connect to the modern pavement, and canons aim out across the magnificently protected bay.

| | The Black Jesus, patron saint of beggars and thieves, and protector of Portobello* * *| Also in Portobello is the Church of the Black Christ, _El Cristo Negro_. Inside is the famous statue of a black Jesus de Nazareno, patron saint of beggars and thieves. The statue came to Portobello aboard a sailing ship bound for Cartagena in 1820. The ship foundered in a storm, and the stature floated ashore. At the same time, a cholera epidemic was ravaging the entire isthmus. When they saw the dramatic statue, the people here believed it was a sign. They promised that if Portobello was spared the cholera epidemic, they would designate October 21 from then on as the feast day of the Black Christ. When the epidemic bypassed Portobello, the miraculous statue achieved mythic proportions. As we sat in the church, we watched villagers stop by for their daily prayer and marveled at their devotion.

| | A mural of the Black Jesus, in a local bar* * *| At 4:00, after waiting an hour for the 3:00 bus, we accepted the fact that wed misunderstood the schedule somehow (bus schedules are only posted _inside_ the buses so, unless youre already _on_ the bus, theres no way to check the timesnot an easy system for simple gringos). So six of us, plus a “taxi” driver, piled into a compact car with no windshield or shocks and pounded over the winding, bumpy road back to Linton. Douglas and Frank sat in the open trunk complaining endlessly of fumes. Once back in Linton, we received the news from Joe that the Fedex from San Andres was in, and that Cecilia would be bringing it with her to Isla Grande in two days. Just like that, it was time to say good-bye to Frank and Lynda, who were leaving the next day, to Lisa and Cade, whod leave two days later, and to Joe and Cecilia, too.

| | Another mural from Portobello, showing mortification of the flesh, or a thief whos been whipped, or what you do to yourself if you sail between Panama to Maracaibo from west to east.* * *| Now, here we are, too quickly. This morning before first light, we heard _Sand_ _Dollar_s engine rumble to life, and around 5 Cade and Lisa coasted out of the harbor, into the swell we knew all too well, and headed back to the San Blas for one night, then on toward Maracaibo. Along with _Street Legal_, _Simba_, and Gringo Joe, whos a ham-radio operator, well talk to them tonight at 9 on the SSB, and every night till they arrive at their destination, just as we all did with Lynda and Frankan ad hoc evening net of friends.

Cade and Lisa know they have a potentially hellish ride ahead, and theyre nervous about it. That kind of distance, all into strong headwinds, stresses a boat and exhausts its crew, and if something goes wrong, there are precious few places to anchor for refuge along the unforgiving Colombian coast. Ill miss these two people very much, especially Lisa, and I worry.

e-mail the Bernons: Ithaka@CruisingWorld.com