Masochism plays a major role in cruising, and for those of us who werent suckled on Marvel Mystery Oil, this is especially true. An incomplete catalogue of the last couple weeks technohassles, all of which required our immediate attention, include: the shredding of the bearing that holds on our dinghy prop; the complete death of the windlass motor (nope, it doesnt have a manual mode); and the untimely and repeated stalling of the ships engine as we entered a reef-surrounded anchorage on the south side of Kanildup. At moments like these I surrender to a loathing of boats, machinery, sailing, and cruising with a bone-deep totality.

| | photo courtesy of Marty Baker| | Kuna huts peek from the trees on many isolated cays * * *| Here in Kuna Yala, there are numerous monuments that remind me of the fine line between good fortune and disaster. Within a mile of us, on the reef protecting our little anchorage, theres a giant tankerhigh, dry and rusting atop the coral; and just across the way from us is the carcass of a Hallberg-Rassy 41, also lying high and dead on the reef, its bones picked clean. I used to thinkwith unattractive, self-righteous defensiveness”Man, did those guys ever screw up big-time.” But Ive seen too many things break at inopportune moments, and now I respectfully mutter, “There, but for the grace of God…”

The other night, Bernadette and I anchored in the East Holandes Islands of the San Blas, at a spot known among cruisers as “The Swimming Pool”because of its incredibly clear turquoise water. There, on a small cay nicknamed Potluck Island, every Monday night cruisers from all over the area gather to share dinner and make a bonfire to burn garbage. Once assembled on the beach, we all arranged our dishes on the teak foredeck of the Hallberg-Rassy; it had been hacked free and installed as a picnic table. Seeing boats on reefs makes me crazily frightened sometimes. Id go bonkers if not for the compensatory delights of clear nights, moonrises, umbrellas of stars, giant eagle rays, hunting fish, and the love of my Commodore (in reverse order, of course!).

| | The sunsets in the San Blas are dramatic, backlighting the pretty beaches and palm trees * * *| Its 0530 as I write this. The moon, full just a few days ago, is still high in the western sky; theres a scribble of yellow streaks spilling out in the east. In front of us, about 300 yards away, are two parallel reefs protecting us from any swell, and eight or nine miles beyond them are the lush mountains of Panama, blue in the dawn light. _Ithaka_ is tucked behind three Kuna Yala islandseach palm covered, and just starting their morning shimmy in a four-knot breeze. Its barely blown in five days, perfect for snorkeling, and weve cooled off morning and afternoon, diving off the stern and swimming to explore the closest reefs. Its eerie to be parked between a lee shore and reefs, but thats the way it is in most anchorages here, so you never completely relax; whenever the wind pipes upas it does for evening squallsone ear is cocked for the familiar lullaby of the anchor chain and the snubber. But ever since the windlass motor gave up the ghost (the day we sailed from San Andres), to save my back weve retired our heavy CQR anchor with its all-chain rig, and weve been using our Bruce anchor, attached to only 25 feet of chain and miles of rope. Most anchorages here are 30-50 feet deep, so these days Im pulling everything up by hand and whining the entire time. As for our windlass, well… thats a nasty tale for another log. With the rode, we hear different sounds and dance to different tunes. Nylon rope has a slightly elastic effect, and minimal weight, so we find ourselves waltzing around much more than we did with the heft of all the chain.

| | This hospitable Kuna girl showed us around her familys cay, and while we were at it, she collected a bag of coconuts that had fallen from the trees overnight. * * *| But before you think Im totally occupied with moaning and maintenance, let me give you a picture of the Kuna, of the paradise that surrounds us, and of our days here. This week, we had an early-morning house call from a Kuna Yala official from the closest check-in point, about 12 miles away. He came by in his _lancha_ and charged us $7 ($5 for the boat entry into San Blas and $1 for each of us), told us some of the Kuna rules, gave us a receipt, and motored happily on his way. This, however, was merely the overall Kuna Yala check-in. We still need to do the official Panamanian paperwork at Isla de Porvenir, but as the Kuna official pointed out, “Theres no reason to hurry over there.” Its also necessary to seek permission from the _saila_ (chief) of each island group wherever we go ashore. The Kuna, who are officially a quasi-independent province of Panama, consider themselves quite apart from the Panamas rules; they have their own local government, customs, and laws for Kuna Yala, “The Kuna Nation.”

The San Blas Archipelago (in Kuna language, it’s Mulatupo) is made up of more than 360 tiny islands. Of these, about 50 are inhabited; a few bustle with busy Kuna settlements and trading centers, but most are temporary homes for a few Kuna families who live there while they guard, collect, and transport coconuts by sailing dugouts (called ulus) to central distribution points for purchase by Colombian traders. The Kuna Yala administer their own lands through a congreso, and they remain a fiercely traditional society. Each village has a nele (shaman, or medicine man or woman), as well as a saila. In some villages, the saila rules powerfully, for example requiring all women to dress in traditional garb. Men mostly fish and collect coconuts; women spend a great deal of time taking care of children, tending to the cooking and home, and doing beautiful needlework molas, which they peddle from boat to boat and on shore. You can’t sit at anchor for more than hour without a visit from an ulu full of colorfully dressed women with their big, white plastic buckets full of gorgeous work; molas sell for anywhere from a few dollars to hundreds of dollars, depending on intricacy and workmanship.

| | The molas for which the Kuna women are famous are worn on the bodice of their traditional clothing, each representing the creativity of its wearer. * * *| The Kuna are a small, dark, handsome people. There’s an almost Asian look to some, and many of the women paint a black line from their forehead down to the bottom of their nose where there’s a small golden ring. They’re thought to be the last of the full-blooded Caribs who were here before the Spanish started mucking things up centuries ago. There’s been scant infusion of outside blood, much familial intermarriage, with its inevitable results, and an unusually high percentage of albinos, who are known as “children of the moon” and much treasured. To see bright white-blond, pink-eyed Kunas running about and playing with their equally dark siblings is a grand sight.

Kuna Yala and Panama have had a fractious relationship; the most recent Kuna revolt, of which folks still speak proudly, was in the early 1920s. Not surprisingly a small group of 5-foot-2-inch-tall men with machetes ran a distant second, and only the intervention of the an American warship helped prevent a grim massacre. In 1925, Panama granted the Kuna the right to limited home rule, but relations remain frosty today, and the Kuna who speak Spanish or a little English repeatedly excoriate Panama and tell us that the Panamanian government always gives them short change.

Several hours and two snorkeling trips after the first official’s visit, the local saila of the Holandes island group, with a couple of buddies, sailed alongside Ithaka in his ulu. He charged us another $5 (the money goes—we’re told—to help support the Kuna infrastructure, including their schools), and he invited us to visit his islands. He presented a waterlogged receipt book and pointed to the space where I should write our boat’s name. With ceremonial flourish he scribbled something (I’m not sure what), and sailed away. Later in the day, he sailed back to Ithaka, his ulu laden with golden mangoes, bananas, and firm avocados. For these, we traded some coffee, powdered milk, and an Interlux baseball cap. Everyone was pleased. He sailed away looking most spiffy—a man with considerable pluck and panache. Sure, he wore shredded duds, has only half his teeth, no motor, a tattered sail, and he has to chase yachties and trade fruit, but he’s still El Jefe, and maybe—as political chiefs everywhere know—the real pay is in what you can pilfer.

| | Kuna woman are extremely shy about being photographed, unless you buy a mola from them or pay them a dollar! * * *| I like traveling to places we struggle to pronounce. We have a small Kuna dictionary that informs us the letters are spoken as in Spanish, but I trip over all the hard consonants and “u” sounds. Go ahead and try saying the next two tongue-twisting sentences out loud: We’re anchored near Ukupsuit Tupu and Kalugir Tupu. Tomorrow, we’ll cut back to deep water, wiggling between the reef and Ogop Piriadup, leaving Quinquindup and Tiadup to starboard on a southeast course to Coco Banderos, where we plan to drop the hook north of Nabsadup, just beyond Tuala, and in the lee of Esnatupile. See? It takes longer to attempt the pronunciation of these islands that it’ll take to get there. The distance is only six miles! With these continuing zephyr winds, it’s likely to be a motor ride.

Assuming, that is, we have a motor, which brings me back to sado-masochism and “The (Other) Story of O” (with apologies to Pauline Reage!). On our way to Ukupsuit Tupu, motoring through rolling, windless swells, we heard Señor Yanmar start to gasp and then choke to dead quiet. In the two years weve been cruising, this was the first time the engine quit when it wasnt the down-line sequel to my having effected some “repair.” Damn! In these moments, I admit, Im not the essence of cool. I raced below and tore the engine cover off with my teeth. Bernadette soothed me by reminded me that the depth sounder showed us in 60 feet of waterplentyand that there were no reefs in the immediate neighborhood. She was right, of course, but still…

| | The dramatic turquoise waters and craggy reefs are everywhere you look in the San Blas. * * *|

The temperature alarm hadnt gone on, so I assumed the engine wasnt overheating due to a shredded impeller or a broken belt. Nonetheless, I could feel my gut churning. The next assumption was that there was air in the fuel line somewhere. (Diesels loathe air.) So I purged the line and we started up again, still not sure where the air had come from. Bernadette turned the key and Señor Y roared to lifefor about 10 minutesuntil we were within spitting distances of reefs, then it died again. I bled air again, and Bernadette got us started. Then, with the Commodore at the wheel and me below, every few minutes, while still putt-putting along, just to be on the safe side, I opened a bleed screw and prophylactically let out more air so that we could get into the anchorage without becoming another San Blas picnic table.

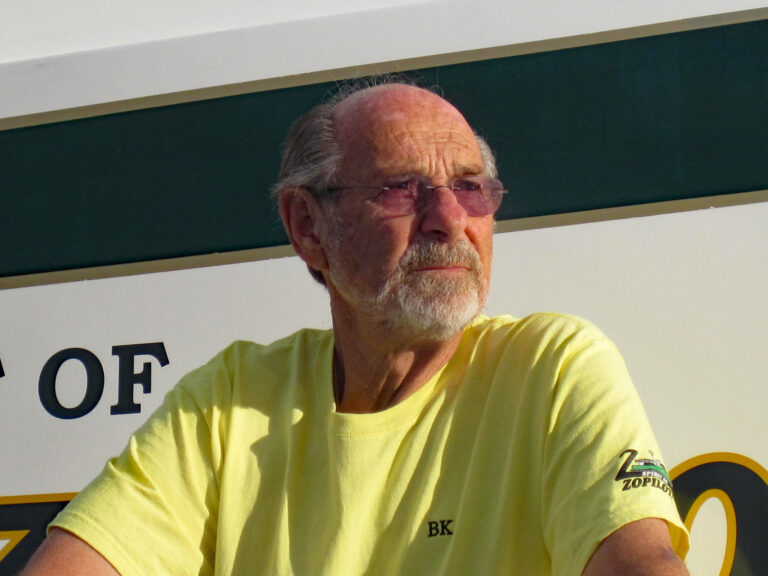

| | Lynda and Frank from Simba, with Douglas and Bernadette * * *| Once anchored, our friend Frank, on _Simba_, dinghied over like a champ, and instead of snorkeling his afternoon away, helped me examine all possible entry points for air into the fuel line. This is a little simplistic, but basically diesels suck fuel from the tank through a series of straws that are linked in sequence, interrupted by a number of gizmos, any of which could have a loose connection allowing in the dreaded air. (Imagine drinking a coke through a straw with a hole on the side—not great suction and you get a bunch of air with your soda.) We disconnected and checked every fitting and hose clamp, finally arriving at the secondary fuel filter. When we disassembled it, sure enough there was a broken O-ring: a hole in our straw and the most likely culprit. Since replaced, Señor Y has been running smoothly again, but when I commit such sentences to paper, I know I’m taunting fate.

Frank and I had sweated in Ithaka‘s cabin for three hours looking for the answer to the problem, and despite the heat, I must admit they were pleasant hours. Ithaka was anchored securely, winds were light, and when I’m working on anything with Frank, I learn a lot, which is a joy. Cruising is like that; it often offers up sublime pleasures from pain, and that’s part of the masochism.

|

| | Kunas are strong sailors. They step the masts for their ulus in a brace, like the one shown, then unroll their tattered sails, sit in a seat at the back of the dugout, and use a paddle as a rudder. In this way, most Kuna men travel many miles from their huts each day to fish and trade. * * *|

|

Still, engines are small potatoesnot life and deathand this past week we were reminded of the difference. For several days, wed been hearing snippets of VHF conversations between two boats anchored in a San Blas island group not far from us. The woman on one boat wasnt feeling well and thought she had the flu or bronchitis. Shed tried a variety of antibiotics, sometimes thought she felt a bit better, would snorkel for half an hour and then sleep the rest of the day. One morning, her husband radioed his friend on the other boat, a retired physician, and asked him to stop over after breakfast. His wife, he said, was “having a little trouble breathing.” His friend raced over and less than an hour later, on the morning net at 0830, the physician asked where to find the nearest medical facility. By the next day, theyd taken their two boats to a small town on the mainland where theres a daily flight to Panama City and its array of good hospitals. A couple days went by; we wondered what happened. Then we found out.

Three days ago, we sailed Ithaka to Nargana, a scruffy little Kuna settlement on the mainland, to pick up some fresh vegetables and fruit. Already anchored there, to our surprise, were the two boats from the radio. The physician’s wife was looking after both boats alone. She dinghied over to say hello and poured out her heart. Her husband had accompanied their friends to Panama City and, there, discovered what he’d most feared. Their friend had been diagnosed with an advanced cancer and was air-evacuated home immediately. Her time remaining, unlike her courage, is severely limited. Before she left Panama, she told her husband and friends that, had she been forced to choose how and where she’d spend her last active week of life, she would’ve chosen snorkeling in the San Blas with her husband.

| | Venado, “deer” in Spanish, and the product of a creative Kuna mind * * *| At dinner last night, four cruising couples spoke of this woman’s tenacity and how ridiculous it is that we all spend so much time complaining about and doing boat projects. You see, it never ends. No matter who we are, where we are, or what we’re doing in life, somehow we still get mired in the mundane—even if we’re living the “cruising dream.” Sometimes I think we’re really awake only when we’re temporarily forced to wrestle with our mortality. It’s hard to be that conscious, and seems impossible to remain so for long, but during those rare moments when we truly open our eyes, we know we’re really alive.

e-mail the Bernons: Ithaka@CruisingWorld.com