How To Train Your Stingray

We dinghied to this shallow area inside the Moorea lagoon, near Taotai pass. Small tour boats shuttle vacationing snorkelers to this spot several times a day. The operators chum with mackerel or sardines and habituated rays and sharks show up by the dozen. It’s a great place to get close to wild stingrays in particular, but not the most authentic experience.

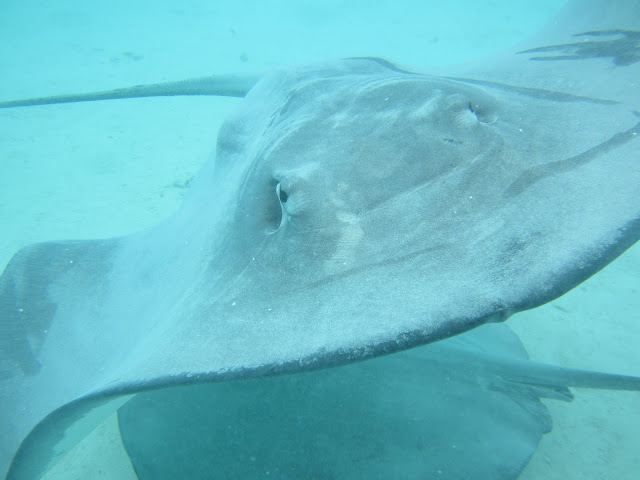

So we got to the spot and there were no tour boats. Frances rolled into the water first. Immediately, three stingrays with 4- to 5-foot wingspans swam up to her, nudging and enveloping her. I didn’t have the camera ready. We all followed her in. Our friends Ryan and Nicole aboard Naoma were with us. They brought a can of sardines. A piece of fish landed near me and rays converged.

Never having touched a stingray before now, I expected a firm-feeling animal with a sharkskin-like surface. Instead I was shocked at how pillowy soft and supple they are. The skin on a stingray’s back makes a baby’s butt feel like 60-grit sandpaper.

They approach like dogs, even seeming to have personalities. Their mouths are on the bottoms of their bodies, about 4 inches aft of their leading edge. So after giving a nudge, they’ll turn upwards and feel you with their mouth. Standing vertically in the shallows, they’d tug on my swim shirt and keep rising up my chest until the front of their bodies were out of the water. I couldn’t help but laugh.

But it was a bit of a nervous laughter. Isn’t this the same animal that ended Steve Irwin’s life years ago? I kept my eyes on the long, rebar-like tails. Yet I knew bus drivers and librarians and honeymooners have been right here, swimming with the same animals, for as long as the boats have been bringing the tourists out.

As soon as I’d push against the rays, they’d respond, relaxing to the point that I could easily manipulate them, moving them to one side or downward. I’d grab the opportunity to stroke their soft topsides, leaving marks where I brushed away a layer of silt, like kids’ hands across a dusty car window.

As the sharks swam around, keeping their distance, the rays seemed focused on getting any food they could, exploring each of us in turn, crisscrossing each other as they swam methodically through the surrounding water, making sure every morsel was gotten. When they decided we had nothing more to offer, they’d retreat about 20 feet and snuggle into the sandy bottom, lined up like parked cars, awaiting the next group.

Where To Next?

Before we left Mexico to cross the Pacific, we wondered where we were headed. After French Polynesia, the possibilities are varied. There is a cyclone season starting down here in November, so that is a big driver in our decision-making process (as it is for the entire fleet).

An overwhelming majority of the few hundred boats that crossed the Pacific this year are headed for New Zealand or Australia. These destinations indicate a route and timeline that are so well-traveled there is a name: the Coconut Milk Run. A few boats divert north from French Polynesia to Hawaii, a stepping stone on a path back to North American shores. Totally adventurous contrarians head further south and east from here, to Patagonia.

For a while now, we planned to do what a few others do, which is to aim northwest from French Polynesia, back up across the equator to Micronesia and beyond. Just two weeks ago, we were on our way to Japan—we planned to arrive April 2016 and we’d already begun making contacts in-country.

But we’ve changed our minds—rather, we’ve studied the information available and decided that the part of the world between here and Japan is not where we want to be during an El Niño event. El Niño conditions exacerbate the ferocity and unpredictability of storms in this already unpredictable area and so…no.

Instead, we’ve decided it’s safer to stay where we are, in the South Pacific islands. Do you see the paradox? We’ve decided it’s safer to weather the South Pacific cyclone season in the South Pacific than to venture into that part of the North Pacific. Of course, that means we may wind up in the path of a hurricane-force storm. Accordingly, we plan to spend a six-month stretch hunkered down in a sheltered spot where our boat has a reasonable chance of surviving a very big storm (and with a plan for us to be safely sheltered ashore in that event).

So why not New Zealand or Australia? In short—and as much as we hope to visit both of those countries in the future—they are too familiar. We are enjoying being where the people are not so much like us and where things happen differently than we’re used to.

So, there are quite a few less-familiar places around here where people on boats do hunker down over the cyclone season. French Polynesia is one option that many French sailors choose, but it’s not an option for us, as the French will not allow us to stay here without the extended visa that was too difficult to get from Mexico and impossible to get from here. American Samoa is another option—and it was in the running for a while, especially because I thought I might have a job opportunity there—but we’ve scratched it off our list. Fiji and Tonga are other options because they’re both comprised of intricate archipelagos that feature numerous protected anchorages. Fiji is especially popular. (They even haul sailboats out of the water there and stick the keels in holes dug in the ground for fly-home-and-leave-your-boat-for-the-season-protection.) That said, we’ve chosen the Kingdom of Tonga.

We will likely show up (it’s still a couple months’ cruising and more than a thousand miles away), sus things out, maybe see about renting a “cyclone-rated” mooring, and stay if we’re pleased. If not, we can make a four-day passage to Fiji and settle there. But I suspect Tonga is where you’ll find us. It’s different (hopefully in a good way), the cost of living is low (we need this), and since they just ran a fiber optic cable from neighboring Fiji, the internet is supposed to be decent—which means I’ll be able to let you all know what it’s like.

In our twenties, we traded our boat for a house and our freedom for careers. In our thirties, we lived the American dream. In our forties, we woke and traded our house for a boat and our careers for freedom. And here we are. Follow along with the Roberston’s onboard Del Viento on their blog at www.logofdelviento.blogspot.com.