It’s that time of year when sailors on both coasts of North America are making plans to voyage south to Mexico or the Caribbean. For many, it’s the first time they’ll put significant miles under their keel or venture offshore. Adding crew can be a sensible way to share the load and keep watch. It can also add to the fun.

A great way to ensure crew are a good fit on board is to set expectations in advance. The approach can be similar to having visitors on board. We adapt a form letter to include our location, the inbound crew’s experience, and the route/conditions we expect to encounter. Sending this letter well in advance helps everyone prepare, and crew can consider what to bring, and ask us questions. For us, the contents of the letter evolved over time (experience is a good teacher); here’s a rundown of the information we typically include.

Packing

Whether experienced or novice crew, they should know upfront what they’ll need to bring and what you’ll have available for their use. You might need to tell a first-timer not to use a hard-sided suitcase, only stowable soft luggage like a duffel bag.

Be clear about the gear they should have. Full foulies, or simple rain gear? Is it cold or wet enough to warrant sea boots? Recommend clothing for the weather you’ll have, and outline how laundry will be done. It’s useful to know before packing what personal care items may be provided (sunscreen, soap, shampoo, etc.) or if they should supply all of their own.

Touch on safety equipment: Should they bring their own PFD, or will you provide one? Will they need a harness and tether? Will a headlamp be useful?

This is also a good time to check in with them about seasickness medication, and make sure they are bringing what works for them. And, suggest everyday comfort items you use that crew might not consider, such as earplugs (for off-watch quiet), an e-reader, earbuds and downloaded media to read, watch or listen to.

Arriving and departing

This can be trickier than non-cruisers realize. We have a saying: “You can pick the place or the date, but not both.” It’s a phrase worth repeating as a reminder of the unpredictability of passagemaking. If your crew is taking time off work to join you, they may feel pressure to keep a schedule—and how unforgiving their schedule is may mean they leave the boat before it reaches the intended destination.

We see this happen with boats sailing south from Puget Sound. They add crew for getting at least as far as San Francisco, but weather patterns mean it’s typically hard to do this in one go. Last year, coaching clients we assisted with weather routing spent 20 days in Eureka, California, waiting for mellow conditions to round Cape Mendocino. Another boat accommodated a long delay on the West Coast by having crew return home for a week of work, and then come back to the boat.

Passage plan

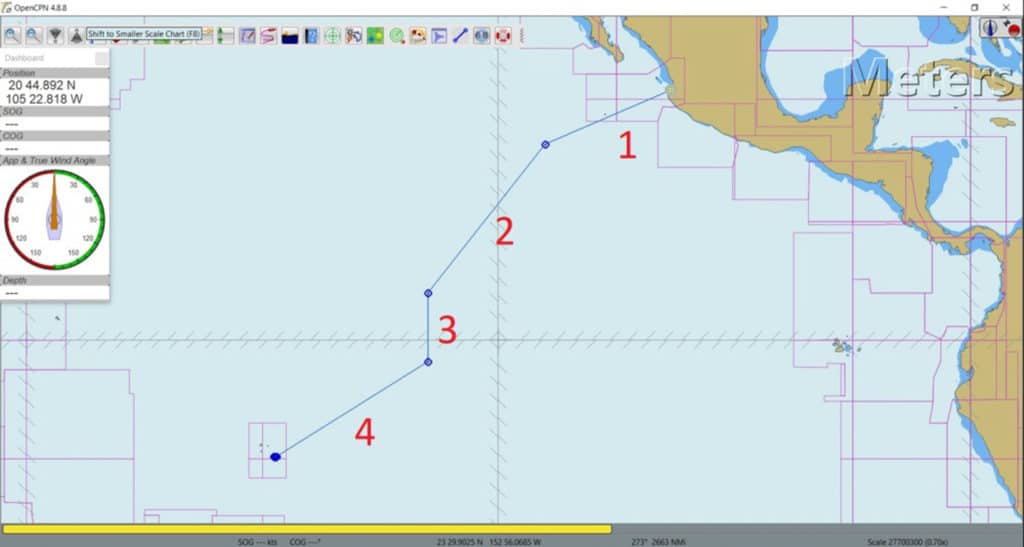

If you’ll be undertaking a passage (versus day hops or gunkholing) with your crew or visitors on board, then you should document the passage basics such as your desired departure date and expected weather, and any contingencies about things like parts on order or projects to complete first.

Most passages have stages to them, and prepping your crew in advance is appropriate to help get them in the mindset. For sailing from Mexico to the South Pacific, we’d describe the stages, from getting off the coast into trades, into a squally zone (and likely motoring) across the ITCZ, to trades again until landfall.

Watch schedule

Prepare crew with a topline view of watch expectations. If that information prompts questions or any discomfort, it can be addressed well ahead of time. Will they be on watch alone, or paired with others? What’s the duration of the watch in daytime or nighttime?

We cover watch routines in more detail separately from this advance letter, but like to make sure we’re all on the same page fundamentally.

Personal space

Where will crew sleep? Provide details about their cabin and berth, and clarify the level of privacy it does or doesn’t have. What stowage will be available? Will everyone share the same head, or do they have a designated head?

Our Stevens 47 Totem has three cabins to accommodate up to nine people with some squeezing. We’d max out at six on board for passages to ensure comfortable sea berths for all.

Utilities

One of the hardest parts of joining a boat for anyone not accustomed to living aboard is managing basic utilities—especially water and power. Give crew a heads-up about how those things are handled. Is water use constrained or at individual discretion? How will they be able to charge devices? Do they need to bring USB cables and 12-volt car charger plugs, or do you have a charging station on board?

Meal routine and snacks

Let them know your typical meal routine, and what’s available for snacking between meals or on watch. Will some or all meals be eaten together? Is responsibility for cooking rotated? What about dishes? Outline how the act of eating is structured, scheduled and shared. Totem has a locker that’s the “OK to snack from anytime, but better not use it to replace meals” including crackers, dried fruit and the like.

This is also a great time to lay out any dietary restrictions, and understand if they have needs to accommodate. I like to find out what a crew’s particular breakfast routine is so we have the coffee or granola or whatever it is they generally choose.

Totem is a dry boat on passages, so we make sure that’s understood. Since alcohol can be harder to get (or costlier) in some places, some boats have guidelines around off-passage imbibing, too. For non-alcoholic drinking, we ask crew to bring their own water bottles. Staying hydrated is important, and counting water bottles consumed is a good way to manage daily intake.

Offshore communication

Set expectations about how communication is handled at sea. Let crew know what they’ll be able to access for messages to and from family at home, once out of cellular range.

Float plan

You’ll want to prepare a float plan, and you’ll need information from your crew to complete this, including their emergency contacts and any medical considerations.

Crew medical

Crew should disclose any chronic conditions. Use the letter to ask that they bring all prescription medications necessary for the expected duration, plus a generous buffer in case unanticipated delays extend their time on board. Refills to prescription medications might not be readily available in your intended destination. Crew should be prepared for this contingency.

Some crew may not be comfortable providing a medical history, and a way to handle that is having it put into a sealed envelope and stowed somewhere, like inside the nav station. It’s assumed they don’t have extenuating medical needs (and if there are any chronic conditions, that those are disclosed in advance). A sealed envelope is only to have available in case of emergency.

After arrival

What happens after you make landfall? Some places are simpler for crew to depart from than others. Crew may look forward to experiencing the destination, or be eager to return home. How long are you comfortable having them stay with you?

When planning our passage to French Polynesia, we let crew know we’ll engage one of the agents in French Polynesia to assist with clearance services. It simplifies requirements for entry and managing crew changes for all.

Costs to crew and the boat

Hopefully, this was clarified before a crew agreement was reached, but if not, spell it out. General rules here vary, because it depends on how much you need crew (and should cover expenses, or even pay them) versus how much they need you (in which case they may be covering their expenses or even contributing a per diem for food). If you eat dinner on shore, is a crew’s meal covered? Are they expected to cover formalities costs for visa, clearance, bond and so forth? Transportation to and from the boat?

In general, we cover all onboard costs, but not crew’s travel expenses to or from the boat. It’s appropriate to cover a celebratory dinner after arrival, too. Outside of that, we generally expect crew to cover their expenses on shore.

Staying safe

This letter to crew is all about clarifying expectations on both sides, but there are other steps in matchmaking and setting up for a good experience. Careful screening on both sides is essential. A safety briefing with all crew when on board the boat is good to have documented, and is best delivered in-person so gear can be pointed out and demonstrated.

Are you heading south this fall, as skipper or crew? Have you done it in the past? If you’d add other information to a crew boarding letter, let us know.